Perfect Match, Part 2: A Kidney Transplant Tale

When my wife Cindy's health declined after two kidney transplants, how would she find a third organ donor? The answer -- which involves my 33-year error -- could make you believe in miracles.

Episode 10 Notes

Perfect Match: A Kidney Tale, Part II

After Cindy's second kidney transplant, we thought her health would be stable. But oh no. That's when some of her most difficult health challenges -- and near-death experiences -- sneaked up on us.

The biggest surprise came in 2014 when our hope was at its lowest point. We discovered a 33-year-error in a particular health record, which led to a sort of miracle.

The photo above of Cindy painting a very large canvas just a month ago shows what stable health allows her to do these days.

Along with her optimism, Cindy's love for creating art was always a key factor in helping her through medical challenges. You can see her imaginative work on her website.

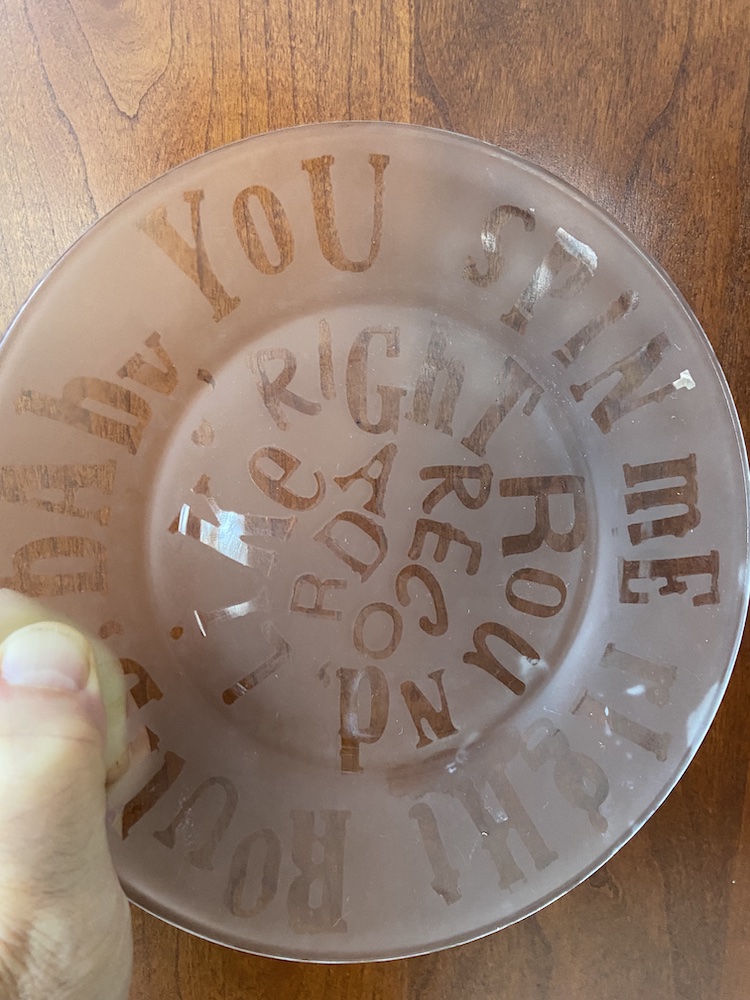

When she's painting, Cindy often listens to music -- and music was a major part of everything we went through together. Cindy etched this glass plate with the words to "You Spin Me Round" by Dead or Alive. We loved that song when it came out, because the beat is so catchy and the lyrics are so silly.

I've made a playlist of all that songs that either entertained us or expressed what we were feeling from 1975 till now.

Listen to our playlist on Apple Music. Or get Youtube links for the songs and get the back story on some of our favorites in my blog post here.

After Cindy's third kidney transplant, we received many cards and letters from friends. They were the inspiration for our podcast episodes.

This one made me laugh, literally till it hurt -- considering that I was so sore after donating a kidney:

And this one made me laugh too...

Here's an example of the kindness we received from so many people -- this note came with flowers:

If you ever want to make a donation in support of the kinds of medical miracles that we experienced, here are some options we recommend:

American Kidney Fund

They get the highest possible ratings from all the groups that evaluate charities. So you can be sure that donations are well-spent.

Lupus Research Alliance

Another highly rated organization, making good use of funds to explore treatments for lupus.

United Network for Organ Sharing

Well-rated organization that works to improve the organ transplant system.

Tufts Medical Center Giving

Cindy got her first transplant in 1980 at Tufts in Boston. This is a general link for donating to the hospital; we couldn't find a specific link to donate to the kidney transplant unit.

UCSF Foundation

Cindy's second transplant was in San Francisco from UCSF Hospital. Again, this is a general link for the hospital, not for the transplant unit (where two of Cindy's wonderful doctors are still practising).

Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center

Cindy got her third transplant here -- the one that involved me too. In this case, you can specifically choose to donate to the Transplant Research Fund – Division of Nephrology

Now that we've told our story, Cindy just has to look at the rest of the items I saved and let me know if she thinks I should shred them. Oh, I hope not.

More info: throwitoutpodcast.com

Listen and rate us: Apple Podcasts

Follow: Twitter (@throwitoutpod), Instagram (@throwitoutpod)

Will anything get tossed? Could happen. THANK YOU for listening!

I Couldn't Throw It Out, Podcast Episode 10

Perfect Match: A Kidney Transplant Tale, Part 2

THEME SONG EXCERPT

I couldn't throw it out

I have to scream and shout

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

END OF THEME SONG EXCERPT

MICHAEL SMALL: Hello Sally Libby!

SALLY LIBBY: Hello Michael Small! And hello Cindy Ruskin!

CINDY RUSKIN: Hi Sally and Michael.

MICHAEL: Today, on I Couldn't Throw It Out, we shall complete the tale of blood, guts, and the fickle finger of fate that we began so recklessly began yesterday. Sally, are you ready for more?

SALLY: Roger!

MICHAEL: To sum up episode one: It was my goal to throw out a thin folder of cards and notes I retrieved from one of my boxes. But can't do that till I tell the whole story behind that folder. This involves more than six decades of fun, challenges, and genuine miracles that made up the life of Cindy Ruskin, and our life together since 1975. We've already gone through two kidney transplants, a marriage, and Sally, how many near-death experiences so far?

SALLY: Okay, so far we have four.

MICHAEL: Just four near-death experiences.

SALLY: Just four.

MICHAEL: So we'll have a lot more of those. But first, we pick up in January 1997 with our migration from San Francisco to New York City, where I had just taken a new job. This is when Cindy and I discovered that a few of our connections had slipped by unnoticed. Remember, Cindy, what we learned from that woman at the bank when we opened our accounts in New York?

CINDY: Oh my God. What we learned is that Michael said, "We are not New Yorkers. We're from San Francisco. We're zen.

MICHAEL: No that's not what we learned.

CINDY: And then he screamed, screamed at the woman at the bank. I need to tell Sally this.

MICHAEL: No, that's not the story. What did the nice woman at the bank tell us?

CINDY: I forgot.

MICHAEL: That we had so many things in common.

CINDY: Oh yes. That's right. The nice woman at the bank said we had so much in common because our birthdates were very similar, our social security numbers were similar – which is crazy because I became an American 25 years after he did.

MICHAEL: Right, and…

CINDY: And we looked exactly alike.

MICHAEL: No. What about our mothers, huh? Didn't the bank lady remind us that their maiden names were almost identical?

CINDY: Oh yes.

MICHAEL: Here's another detail, Sally. As I told you, Cindy and I grew up more than 7000 miles apart.

SALLY: Yup.

MICHAEL: But our cousins helped us figure out that the town where my grandfather was born in Lithuania… was only about 120 miles from the town where Cindy's grandfather was born in Latvia.

SALLY: Oh wow. That is crazy.

MICHAEL: Well, that's like the distance from Baltimore to Philadelphia. It's nothing. And they had trains between the towns back then, by the way. So it's not impossible that our families crossed paths back in the old country.

SALLY: Whoa.

MICHAEL: So Sally -- you decide if this stray fact becomes more relevant as we continue our tale.

SALLY: Yup. That's a woo-hoo moment.

MICHAEL: So back to New York in the late '90s. Things definitely seemed better with Cindy's new kidney. We had many good times that never would have happened otherwise. On the other hand... this was not what most people would call normal life. Cindy was very energetic in public. She was doing so much. She was teaching art classes for students all over New York City. But we had a little secret which is that sometimes she would be so exhausted from all of that that she'd go to bed for days. Even as the science got better, her immune system had to be suppressed to keep her from rejecting the kidney.

SALLY: How many drugs was she on?

CINDY: Three immune-suppressants. But then, you know, on other drugs because my kidney function dropped a little bit. So my blood pressure started to rise and I had to take blood pressure meds and the usual stuff that people do when they get older but I did when I was younger.

MICHAEL: But in any case, her immune system was suppressed and the kids she taught were carriers of every germ. It was kinda one thing after another. Cindy would say, "Oh, I have a little sniffle." Then she'd be down for two months with the worst cold you ever knew.

CINDY: Or pneumonia.

MICHAEL: Or pneumonia. Many people don't know that immune suppression also allows skin cancers to grow. I'm gonna say a number that I want you to ponder for a minute, Sally… Since 1987, the number of skin cancers that a doctor has carved off of Cindy is... more than 90. Think about that. More than 90.

SALLY: But how many surgeries.

MICHAEL: 90

CINDY: By carved, which is a bit of an overstatement, he means removed, which means Mose surgery, it means excisions, it also means scrape-and-burning.

SALLY: I cannot believe that.

MICHAEL: Yup. Sometimes they were small. But often – including the past few weeks – she's go huge gashes that don't heal for months. Sometimes they were large gashes that didn't heal for months.

CINDY: Well, if they're on the lower extremities, the lower leg, they really take a while. And especially if they're big.

MICHAEL: Now if I get a pimple, we will talk about it for weeks. And there will be a lot of moaning. Cindy doesn't even mention it. She comes skipping out of the dermatologist's office. Partly, she knows things that are much worse. During our first two decades in New York, there were MANY incidents. Any of these incidents on their own might have been enough to end the game for someone a little less strong than Cindy

CINDY: I would say "lucky."

MICHAEL: Yeah. I know you don't to think about these things. But to get where we need to go, I think we need to share what happened. So I'm gonna give you little memories.

CINDY: Uh oh.

MICHAEL: And you can riff on them.

CINDY: Okay.

MICHAEL: Ah, I'm gonna start in 2000. The year 2000. I was waiting at a restaurant on 5th Street. You were supposed to meet me. What happened?

CINDY: Those were the days where they had those sandals that were like rubber platforms and there was an elastic thing over the top. I'm not the most coordinated person. And my ankle kind of slipped slightly and I fell on the sidewalk and broke my ankle.

MICHAEL: Yes.

CINDY: People carried me back to my building because it was very close to the building. But Michael was waiting for a long time.

MICHAEL: Yeah. Didn't have that dinner. She was in a cast for two months. And she has another side effect of kidney failure Brittle bones and osteoporosis.

CINDY: All the things that happened to people when there were older happened to me in my 30s. I lost my hearing. Actually, I probably lost that in college.

SALLY: You still have your teeth.

CINDY: Well, one of them…

MICHAEL: We gotta get to that one Sally. You keep getting ahead of us. So skip to 2004. Ten years after Cindy's second transplant.

CINDY: It's nine years after.

MICHAEL: She goes to the nephrologist…

CINDY: He said, "You're losing your transplant and probably having a rejection." And I said, "Well, shouldn't we biopsy and see what's going on?" And he said, "No. Nine years is a good run." Which I thought was crazy. I was like, "We're gonna do nothing?" So I called the San Francisco transplant team and said, "They say I'm losing my kidney and that I should just accept it." And they said, "We can still turn this around. Get on a plane and come out here immediately." So I flew out to San Fransisco. Love those guys. Because they diagnosed me with APLS. The anti-phospho-lipid syndrome. Basically, what was happening is little tiny clots were forming in my kidney and it was destroying my kidney. I then had a wonderful lupus doctor in New York. He said, "You need to change doctors immediately. And he recommended this amazing doctor – Dr. Gerald Appel at Columbia. He re-tested and said, in order to get rid of those little clots, I had to go onto Warfarin or Coumadin, a blood thinner. Which created many adventures of its own.

MICHAEL: Okay, we'll get to those. I think one thing that is worth skipping ahead to say is that Dr. Gerald Appel allowed Cindy to keep that kidney much longer.

CINDY: Another 11 years.

MICHAEL: Yeah. So he was kind of a miracle worker and we're very grateful to him. But let's skip to 2005. So now we've had the fall and we've had the kidney biopsy. In 2005, I had invited some neighbors to our apartment and Cindy felt that the paintings on the wall needed to be rehung. Now Sally – do you rehang your paintings before guests arrive?

SALLY RESPONSE

MICHAEL: And what happened next Cindy?

SALLY: Ah, infrequently. But I try not to.

CINDY: But you didn't paint the paintings.

SALLY: Right, right.

CINDY: And besides, I like redecorating. It's a project.

MICHAEL: So Cindy, what happened?

CINDY: Oy. He's gonna make me tell this story.

MICHAEL: Well, I'll tell some of it if you just…

CINDY: So this very heavy large painting on wood fell on my foot and created a massive gash in my foot.

MICHAEL: Do you remember which painting it was?

CINDY: I don't remember which one. Was it the blue one?

MICHAEL: Oh, I was just thinking we could charge more for it. But at the time, she

said it was nothing. A little bump.

CINDY: Well, because the guests were coming.

MICHAEL: I know. This is a repeated theme. Oh, it's always nothing. So Sally – before I even tell you, you can just mark down a near-death experience.

SALLY: All right.

MICHAEL: From a painting. The wound on Cindy's foot opened up into a gash two inches around. After my guests left, we ended up in the emergency room. I think that now it is appropriate for us to talk a little bit about emergency rooms where we spent so much of our time. If you add it up, Cindy has spent many weeks – maybe even months of her life – in emergency rooms. In New York City, this meant we'd go through the lobby, past big signs that told us we were in one of the best hospitals in the world, and then we'd enter… hell. Total chaos. Danger. A living nightmare. It's amazing that wonderful medical workers are so committed to helping other humans that they choose to work in emergency rooms. But the conditions for them and for everyone who dares to cross that portal are truly horrible.

CINDY: We haven't been to every single one.

MICHAEL: Okay. Every one we went to. We've been to, like, five. What happens is, because of our health care system, the poorest people have no coverage. So they use the ER as their doctor's office. Emergency rooms that were built for maybe 50 patients could have 150 patients in them. Maybe. The beds are lined up all along the hallway. And you know those bays where there's supposed to be one bed with a curtain around it? There would be three beds in there. This was long before Covid had emergency rooms full. Donors give to the hospital and they give fancy wings with their name on it. But hospitals can't make a lot of money off the emergency room. So they don't generally invest a lot of resources in it. Here's Cindy. She has no immune system. She's crushed into a bay with two other beds that are inches from her, basically touching her bed. And we don't know what diseases the other people have. The other thing that happens is the main hospital is always full so there are no beds for people. To get into the main hospital, you have to first go to the ER. And then you wait until there's a bed. I would say we saw this at least 15 times in different emergency rooms. You're really sick. And you don't wait eight hours to get in the hospital. Or 12 hours. After Cindy dropped that painting on her foot, she was in the Weill Cornell emergency room for... THREE DAYS. Three days.

SALLY: Oh my God!

MICHAEL: And none of the following is an exaggeration. None of it! During that time, as I said, her bed was squished between two other beds, inches away.

CINDY: No, they stuck me in a hallway.

MICHAEL: She was in a hallway also. Her sheets were never changed. For three days. She was never brought a meal. For three days. I brought all her food.

CINDY: And food for the other people.

MICHAEL: It was incredibly painful for her to walk. There was no one to help her. When she needed to go to the bathroom, either I helped her or she did it on her own. And then, Cindy – who was severely immune compromised – shared a bathroom with hundreds of other patients. With every kind of disease. Every kind of human filth on the floors, on the walls. The doctors would come by and they'd say, "Yeah. Her wound is infected. Yeah, the wound just grew by 20 cm." They'd give her pain killers.

CINDY: I think they gave me some antibiotics.

MICHAEL: Maybe some antibiotics.

CINDY: But they didn't kick in.

MICHAEL: But she stayed there. And the wound got redder and redder. And we could see it moving up her leg.

CINDY: It's like blue line.

MICHAEL: And I would try to find out what was happening, try to get help for Cindy. But I couldn't succeed. On the third day, I saw a doctor at the doctor's bay, and I said, "This cannot continue. My wife is in danger . Something has to be done!" He looked at me with this totally sarcastic look of "Oh I'm so scared." And he jumped back, and he turned his back to me and went back to his paperwork.

SALLY: Oh, what a dick.

CINDY: That's not typical. Emergency room doctors are really saints.

MICHAEL: Yes, we're gonna get to one of those. Anyway, when Cindy got a hospital room after three days, the doctors clustered around. They were very concerned. And then they said to me, "This is really much worse. We have to consider amputation."

SALLY: NO!

MICHAEL: Amputation! For a painting that fell on her foot!

SALLY: Oh my God!

MICHAEL: She was in the hospital 12 days. The wound took I think three months to heal. For anyone who says that this country can't have better emergency rooms, excuse my French. But go fuck yourself.

SALLY: There you go!

MICHAEL: And that was just a blip. 'Cause then we get to 2008. That was a fun year, Cindy.

CINDY: That was not a blip.

MICHAEL: Let's see. In 2008, there was the cyclist who ran into you while you were trying to get a cab – and, those brittle bones -- a broken humerus. Sally, c'mon with the joke. C'mon.

SALLY: You've got me speechless.

MICHAEL: C'mon.

SALLY: Can't do it here.

MICHAEL: Oh, you were supposed to say that there's nothing humorous about it.

That was a very painful thing. It took months to heal. Then she also had extremely painful and severe gout, which made it at times almost impossible to walk.

CINDY: It was agony! And we didn't know it was gout. Because it didn't look like gout. But I went to an acupuncturist and they put a needle in and then this stuff started coming out. They went running away.

MICHAEL: And then there were hospitalizations for aurinary tract infection, a stomach virus, a bronchial infection.

SALLY: Oh Cindy.

MICHAEL: All of which required going to the ER and repeating a variant of what I've described. Just as Cindy was saying before, there's one exception. One day at 3 AM, we ended up at the New York University emergency room. Cindy felt so terrible, we couldn't get her to her usual hospital. So we came in. And we seemed to catch the eye of a doctor who seemed harried and tired. But she was clearly a manager. She was giving directions. I was a little bit nervous when she came over. I thought she'd kick us out or discipline us or something. But instead, she asked us for our story. And then she said, "You two have been through so much. Come over here." And she looked around to make sure no one was watching. And she said, "You both need to rest while we find your doctor. No one here needs this more than you do." She put Cindy in one bed. She put me in the other bed. She put a curtain around us. And she put us to sleep.

SALLY: Oh my God. That's so adorable.

MICHAEL: And when we got home from the second hospital we went to, the phone rang and it was that same doctor. She called to see how we were.

CINDY: She had noticed we had left before she came over.

MICHAEL: And we later found out that she was head of that emergency room. And if there is justice in this world, she is now retired and living the most wonderful life.

CINDY: I wish we knew her name so we could give her a shoutout.

MICHAEL: And feeling our gratitude 'cause it was amazing. It was one of the most amazing things.

CINDY: And such compassion. You know, she took the time. I mean, she had heart attacks and other things going on around her that were just…

SALLY: Think how much she's seen and been through and here she looked at you two and – AH! Emergency!

MICHAEL: Anyway, there were kind moments. That sort of tempers what I said earlier. That's the same year Cindy got something called MRSA. Can you explain what MRSA is Cindy, and why it was a big deal?

SALLY: Is that a skin-eating disease?

CINDY: MRSA is an infection that doesn't react to antibiotics. I had a skin cancer that was sort of an open wound and I think it's very possible that the infection got in that way. I was getting so many infectious diseases that year. It was one trip to the hospital after the next. That entire year, we just kept going to the hospital and being admitted. I'd never heard of MRSA because it was long before… you know, now a lot of people know what it is and there are some treatments. Didn't you have to glove up? All the doctors came in like suits, with their faces covered and their heads covered.

SALLY: Yes. Very contagious. I think you can even get it in a shower.

CINDY: I think that's very possible.

MICHAEL: But in any case, for someone who was immune-suppressed, this was really serious. There was no cure. And this could have been the end. So Sally, add another notch to the list.

SALLY: Okay, MRSA. Mercy, mercy, me.

MICHAEL: It was horrible. We were so naïve, though, because we didn't realize that things could get worse. There were also "the bleeds." And Cindy, can you just explain why the bleeds happened?

CINDY: Well, remember I was taking Coumadin or Warfarin for the anti-phospho-lipid antibody in order to save my kidney. That meant that if you fall, you're going to bruise very badly. And you don't clot. Yeah. It takes a long time. And I'm a kind of clumsy person.

MICHAEL: But the first really bad incident had nothing to do with Cindy's clumsiness. There was a really nice doctor. But she did not know that when she prescribed antibiotics for one of Cindy's infections, it would quadruple the effect of Cindy's blood thinner. So the artery in Cindy's leg?

CINDY: We don't know. It was my abdominal…

MICHEAL: The abdominal artery just opened up. Now we've told you about a lot of things that went on. But if anyone hearing this thinks they understand pain, this is a whole other level. Because Cindy doesn't even notice if you cut a seven-inch hole in her leg. But when you are bleeding internally…

CINDY: And the weight of that blood is on all your organs. You know how doctors say, "What's your pain from 1 to 10?" And, you know, I was always like 4, 5…

MICHAEL: Two.

CINDY: I'd never got to 8, I think. And then all of the sudden, it was like… I know what a 10 is. And to this day, I know what a 10 is. It was absolute agony. First, they started giving me more blood because my blood level was down, because it wasn't in my veins, it was in my abdominal cavity. And in my legs.

MICHAEL: So because they were giving her more, she got more and more blood in her abdominal cavity. Eventually she had… 40 pounds of blood… 40 pounds of blood in her abdomen. They couldn't give her enough pain killers. She was screaming. Eventually the doctors, I don't know, they went away – I don't know what happened. The nurses said they had done everything they could. So I tried the only trick I had. I went to the doorway of her room, and I stood there – I told you I had become a cryer -- and I just sobbed. I stood there where everbody could see me. And I would not move. I stayed there and sobbed and somebody walked by and saw it because they got the doctor in there and Cindy got more morphine that I guess you're supposed to get.

CINDY: We don't know but…

MICHAEL: But anyway, they eventually did an operation to remove the blood and eventually she recovered. But Sally this is another notch for your near-death list.

SALLY: So we're on seven now.

MICHAEL: The bleeding happened again and again. This got repeated. Cindy would say she was fine. "Oh, it's fine. I don't have anything. It's nothing." Then in the middle of the night, we'd realize it was not fine and we'd be back in the ER.

SALLY: Cindy?

CINDY: Yeah.

SALLY: This may be a tough one to answer. But I'm just wondering after all the health, medical, emotional turmoil – and one thing after another – did you ever think, "I can't do this anymore? I just want to check out."

CINDY: Good question, Sally. I definitely have at least one or two friends who did exactly that. And I knew then that I was someone who wanted to live. And I think in order to survive like this, you have to really want to live – and be lucky. I don't think I ever lost that.

SALLY: You had to deal with a lotta lotta pain. Physical pain – and emotional. Did you develop any mental tricks to sort of transcend the pain? You had drugs but…

CINDY: Yes, I definitely had drugs.

SALLY: That helps.

CINDY: You know, when I had that huge bleed, Michael brought something in that really helped. And it was amazing. It was crossword puzzles. I'd never done them. And just having your mind busy on something that you could sort of obsess on. 'Cause I couldn't read. The pain just wiped out any kind of concentration except bloody crossword puzzles. An extraordinary pain reliever for me. I think distraction in general. Like, if I'm not feeling well and I start painting, I completely forget that I was sick.

SALLY: Did it make you spiritual at all? Did it give you ideas of what may lie beyond?

CINDY: Michael is shaking his head vigorously. I think I explore those things in my art. The magic of our existence.

MICHAEL: You're certainly not religious.

CINDY: Yes. I'm definitely not religious. After this kind of reality, it's hard to get religious. I'm actually very jealous of people who are religious. Because they think there's a reason. It helped me most of all to come to peace with my own death very very very young. And it's hilarious for me to watch Michael only start to figure out that life is short now…. when in college I was completely resigned to the fact that I probably wasn't going to make it through my 20s. That piece has been there always – that it's okay to die. So when I'm in these terrible situations, I do always say to myself, "It's okay."

MICHAEL: I'm struggling with Cindy saying that she was okay with the idea of death. If you ever had been in the hospital room with her, that is a person who was NOT going to be checking out. Her will to live is rather strong.

CINDY: I didn't say that I was ready to let go. I said I was at peace with the possibility. But as long as I can hold on, my life happens to be incredible. Besides my health, I have a phenomenal life. I'm very very blessed in almost every way, except my health. To me, it's worth fighting for.

MICHAEL: And, on that note, we gotta get back to our story. Because the fight was far from over in 2008. The next few years were a little calmer. There was a bone biopsy in 2009.

SALLY: Do you have this written down, like the dates? Or is it all just in your head?

CINDY: Michael looked at my medical records.

MICHAEL: Yeah. I checked her medical records so I could have some notes. Then we go to 2012, when an oil truck failed to mark a hose that was pumping oil into a building. Cindy fell over the hose. She shattered her jaw. She broke a rib and – getting to the teeth – she knocked out three teeth.

SALLY: Oh my God, Cindy.

MICHAEL: And that set her back quite a bit.

CINDY: There were more amazing people in the emergency room. I think that was NYU again. There were fantastic dental people. One tooth was like hanging from a string and they actually put it back and now it's in there as had as a rock. It's dead. But it's there.

SALLY: Now didn't you have to take your meals liquid, because of your jaw being wired shut?

CINDY: Probably. I don't remember anything.

MICHAEL: She didn't look too good after that. It was a little scary looking. A little Frankenstein-ian. And then, of course, there was 2013 – which brought some more excitement. This was not actually the worst thing that ever happened. It was just the most horrible to see, which is that from those blood thinners, Cindy got a bleed in her nose that would not stop.

CINDY: And by the time Michael got home, I had bled all over the walls, the floor. I mean, I couldn't stop this thing.

MICHAEL: There was blood dripping from the light switch.

CINDY: It wasn't a big deal. But it was just nuts the amount of blood that came out of my head.

MICHAEL: So we went to the emergency room and she looked so horrible that people gasped and ran.

CINDY: I got attention immediately because they needed to get me out of the emergency room where anyone could see me. 'Cause, I mean, the blood was just gushing.

MICHAEL: So this is a pro tip: If you need to get through the ER in New York City, blood increases your rank. Okay, so there was that. Then the same year, Cindy was working on installing a mosaic at the Lower East Side Girls Club when I guess about an 8-foot metal ladder fell on her head. And that's another one for your list, Sally. A head concussion. You're on blood thinners. That was a near-miss.

CINDY: Okay, of all of these, I would say this is the one time I thought I was gonna die. It was so absurd. I was sitting eight foot away from this ladder. Someone opened the door and the ladder fell on the person-on-blood-thinner's head. Head! When we got to the ER, the triage people ran with me – I mean, ran. Because we all thought I could be bleeding into my brain. And I was actually thinking, "Should I call Michael and say goodbye? Or should I wait and see what happens?" But with this, I really thought it could be the end.

SALLY: At this point, though, did you think, "Somebody must have put a curse on me?" This is unreal. It's, you know, hard to believe!

CINDY: No, because I survived. I feel like I don't have a… Well, maybe I do now because it's ridiculous. People I've met through this journey are no longer here. I feel like I'm a survivor. But… I'm really tired.

MICHAEL: What happened was that Cindy kept bouncing back. But, around 2013, she was beat. It got harder and harder to live a normal life. And then we got the inevitable news. Which is Cindy's nephrologist told her that they had saved her kidney as long as they could – it had been nearly 20 years…

CINDY: It was 20 years. We knew my kidney was failing. So that's why I was slowing down and feeling worse as I was going into kidney failure. He said, "You've reached the point where you need to go on the transplant list." And the list, it was like a five-year wait, I think.

MICHAEL: We were pretty desperate. We could not do another five-year wait. We just could not do that. We could not. At the same time, as you heard before, no one in Cindy's family was the right match. I couldn't donate because I was the wrong blood type. I knew this because the Red Cross gave me a blood card when I donated in college. It confirmed I was AB-. That meant that I was very limited as a donor. I could give only to AB- people. But, when we got down to the wire, the doctors told us about a new option. Computers had advanced. It was now a point where you could put the data in for a whole bunch of people and it would do a round robin match. I'd give to one person. That person's partner would give to someone else…

CINDY: It wouldn't necessarily be a partner. Every person who needs a kidney brings a donor to the table. And they try to match them up, and there have been some very successful ones which were like six transplants in a row.

MICHAEL: I was scared. It was a scary idea to me. But we agreed that it was time for a new project. And it was a crucial project. So I went in and I got tested so I could put my name into this pool of donors so that I could do this round-robin trade. That was a low point for us. We were really beaten down. And our friend EZ did something really wonderful for us. He had a country home on a hillside in Sonoma California – it's the wine country north of San Francisco. And he gave it to us for a full week.

SALLY: Nice.

CINDY: Oh my God. It was heaven. Heaven.

SALLY: Oh, I bet.

CINDY: Had no phone service. Well, very limited.

MICHAEL: That's the one flaw. It's really one of the most beautiful places on earth. It's like Italy, only in California. Cindy was so sick, we went up that hill and we did not come down. We brought our groceries. We stayed there. We just wanted a week without medical stuff. We just wanted one week. After that week, when we drove down the hill, Cindy saw on her phone…

CINDY:… that there had been a couple messages from Columbia -- transplant team. I called them because I'm very very difficult to match. If they found a good match for me, we should take it. In the old days, if there was a kidney in Texas, they would fly it to San Francisco. Now they don't fly it anymore. There's just too big a list. So they give it to local people. So the guy said, "I have a kidney for you." And I said, "I'm in California. Do I have time to fly?" And he said – God, this is so emotional – he said, "No. Your donor is alive." And I was like, "Alive?" Then I thought, "Oh the round robin." Michael had heard nothing – nothing from them. And I was like, "Alive? Wait. What do you mean?" And he said, "Cindy, your donor is your husband."

SALLY: Oh, that gives me chills.

CINDY: I was like, "It can't be. He has the wrong blood type." And they said, "No, he has the right blood type.

MICHAEL: My blood card… was wrong. For 35 years. I was not AB- . I was O- , and that's the universal… (starting to cry)

SALLY: Oh wow. Tears all around. This is amazing.

MICHAEL: That's the universal donor. But that's not the key detail. The key detail is something else.

CINDY: When I was on dialysis when I was in college, there was a theory back then that if you had blood transfusions, your body would get more used to taking in foreign things and it would help you with rejection. What it did is, it made your immune system SMARTER. But we didn't know that back then. And I was getting regular transfusions to help me prepare for a transplant.

MICHAEL: So she had a very high amount of antibodies in her blood. When they'd test kidneys for her, her body – as I understand it -- had many ways to attack…

CINDY: Reject.

MICHAEL: And reject. That's one reason why it took five years to get her second kidney. The odds were terrible. Maybe 1 in 10,000 chance of a perfect match.

SALLY: One in ten thousand chance of the perfect match.

MICHAEL: Something like that. And when they tested my kidney…

CINDY: I said, "What about the antibodies?" He said there was no antibody reaction. And I was just like, "It's not possible."

MICHAEL: There was no antibody reaction. And… that weird-lookin' girl that I saw in the hallway of her dorm in 1975…

CINDY: And you were standing at her bedside, telling her jokes and stories. And little did you know. Wow.

MICHAEL: And those ancestors who were miles apart. After all those years and all those troubles, we were a perfect match.

CINDY: My favorite part of the story was my mom saying that I should marry Michael. And as my aunt said when I told her that Michael was a match, she said, "It's bashert." Which means it was meant to be. "Your mother knew it was meant to be."

SALLY: Awwww. Bashert. It really is a hero and heroine's journey.

MICHAEL: Oh, don't get…

SALLY: Michael doesn't want that.

MICHAEL: Remember the whole story, Sally. So then I started doing my usual control-freak planning. I thought it was a bad idea to do the transplant in the summer. Because it would be so hot. We'd be in an apartment. W e'd be cramped inside. I planned it for the fall.

CINDY: He's planning…

MICHAEL: And the Dr.Appel gently pointed out, "Um... Cindy is gonna die."

CINDY: While you plan! This is not about your plans.

SALLY: Couldn't you have gotten AC for your apartment?

MICHAEL: We did. We got a new air conditioner. And that was another story. Because it was supposed to be quiet and it was very noisy. But on July 1, 2014,

two days before Cindy's 57th birthday, we went into the hospital together. We were in separate prep rooms. My sister Debbie was there to keep me laughing.

CINDY: And my sister Karen was with me.

MICHAEL: And they rolled me by Cindy and into the operating room. For those of you who have never been in an operating room, or don't remember… I don't know about… Sally, have you been in an operating room?

CINDY: They've changed.

SALLY: Operating room? Only for kids. But that's not really…. Well, that's an operation.

MICHAEL: Yeah. It is an operation. I was surprised. It's freezing cold in there. And you're wearing almost nothing. And they don't put you on a nice bed, like they put you on a stainless steel kind of shelf, which is also very cold.

CINDY: It was different from any other surgeries I've had in the past. It was like, yeah, the sides of the bed are gone.

SALLY: Sounds more like a morgue.

MICHAEL: I got on that shelf, I realized that I just waved to Cindy, and she might die. And I might…. And I might never see her again. And the nurse said, "You seem very agitated. What are you worried about?" And I said, "Cindy! Don't let her..." And then I guess they decided I shouldn't finish my sentence. That's all I remember.

CINDY: I think Michael was definitely… was overreacting. Because, you know, I thought that this was incredible that I was getting my life back. One thing I didn't tell you when I was talking about how bad dialysis is and how awful you feel in your body is that the minute your transplanted kidney starts working – which in my case, all three times was on the operating table – you feel fantastic. You feel amazing. It's the most extraordinary thing. You had no idea how sick you were. Because amazing is over-the-top amazing. It's just unbelievable. Everything tastes so good. Everything feels so good. Your body feels good. Despite all the drugs, despite anything. Of course, with the second transplant, I ended up in a wheelchair. There were always issues that happened afterward. But when you first wake up and you think, "I'm never going to forget this feeling." And, of course, eventually you do.

SALLY: About how long after the operation?

CINDY: Minues. Seconds after.

SALLY: Really? Wow.

CINDY: The minute the kidney starts working, I felt better. Ultimately, it is mind-blowing. I don't think it's luck to have had it three times. But it's miraculous, and…

SALLY: And when was the last time you had ever felt that way? How far back?

CINDY: Well, the transplant before.

MICHAEL: Sally, did you get a chance to watch the video I sent you? What did you think?

SALLY: Yes. I liked it.

MICHAEL: It was called "Wait for Me." It's from Hadestown, which is the story of Orpheus going to hell to meet Eurydice, to try to save…

SALLY: Yeah. Right.

MICHAEL: ...to try to bring her back.

SALLY: Yeah.

MICHAEL: And when I think of that day, it's the best way I can explain it. It's like Cindy and I traveled to another world and we came back again. And… and… you know, music was a big part of what we went through all those years. So I made a playlist of all the songs that were important to us, and I put them on the website at throwitoutpodcast.com.

SALLY: Cool.

MICHAEL: But that's the most important one. The next thing I remember is I opened my eyes and there was my sister Debbie in the recovery room. She was ready to make me laugh again. It hurt a little.

CINDY: It hurt a lot!

MICHAEL: And another person I really wanted to see, who was my friend Gay Daly. She was my officemate from my first job at PEOPLE magazine. She had given a kidney to her husband Jay, who was my editor at PEOPLE. And to see her was very comforting. Cindy was still in surgery. But Debbie told me later that the doctor came out to them in the waiting room and told them, "Don't worry about a thing. That kidney is pissing like a race horse." So Cindy and I both came out of that surgery a lot better. I was in some pain. But I had almost no wound. They slurped that organ out of you laparoscopically, through a tiny little hole. They also extracted a lot of my worries. And Cindy had a new kidney that matched her perfectly. The fairy tale should end right there. But because it's Cindy, there are a few more blips before we hear the Disney music. Cindy – tell about your state after the operation.

CINDY: Oh God. Okay, there have been a couple of moments in my life where there have been some medical people who have not been good. In this case, it was a physician's assistant who didn't come see me and I was screaming in pain again. We did the surgery on Coumadin. So it was number-10 pain, because I was bleeding into the bed of the kidney. And she gave me Tylenol without seeing me. And when I screamed and said I needed more Tylenol, the nurse said, "Well, it will cause liver damage." And I'm like, "Fuck liver damage! You don't understand. It's pushing on my bladder, which is full. And I cannot pee." But they went in. They couldn't find the hole where the bleed was happening. But they lined that whole area so that the hole was covered and removed all the blood. The doctors were amazing and dealt with it immediately.

MICHAEL: Didn't we have to go back to the hospital once for the bleed?

CINDY: I think we did.

MICHAEL: I think we did. Well, anyway, it got resolved. And we're getting near the shredding moment. But we have a few more twists to keep it exciting. Turns out, the transplant jostled – for me -- a congenital heart problem that I didn't know I had.

CINDY: If they had known about it, he wouldn't have been a donor.

MICHAEL: Yeah. So I had a tachycardia that had never been detected. I went back to work and I just said, "Oof. I don't feel so well." After a week, I went down to the nurse's office at work and they took an EKG right away. The next thing I know, I'm in an ambulance. Once again, there weren't enough beds. So I was sharing a room with an older woman who watched Fox News all day. Every time Obama came on, she shouted out "putz!" This wasn't good for my heart. She was also on the phone, complaining about me. "That putz! Marching around my bed like a soldier!" Anyway, eventually they did something called an ablation. They stick wires through your groin, goes up your arteries and then zap your heart with some electricity, and it stops the irregular beating. And it worked! Things were looking up. Until December of that year when our peace was shattered yet again. This time, by my freaking violin. The violin had caused so much trouble in my life. And not just because of the terrible sounds that I made with it. I was taking lessons again, and Cindy somehow got her foot caught in the strap of the case and she crashed down into the wood floor.

CINDY: And I was still on Coumadin.

MICHAEL: She said it was nothing, of course.

CINDY: No, I didn't say it was nothing. I just said, "It's not broken."

MICHAEL: You said you were fine, and then the pain got so bad…

CINDY: …the next day…

MICHAEL: …that we had to call in the EMT folks to carry her, and it was so bad that we couldn't even go to the hospital we should have gone to. We went to a closer hospital.

CINDY: And that was a big mistake.

MICHAEL: Yes. They found out that she had broken her hip. December after the transplant. And the surgeon did not do right by us.

CINDY: I wish I had his name to because I would like to tell someone to not ever go to him. He was one of the worst doctors I've ever had. He never saw me after the operation. I bled into the hip. He wouldn't let me leave the hospital. Dr. Appel was trying to get me to Columbia, trying to get me out. He wouldn't discharge me. I should have just got up and walked out.

MICHAEL: Couldn't walk.

CINDY: It doesn't matter. We should have wheeled me out. Ultimately, I was forced to have a second surgery when I knew that I was probably going to bleed back into the hip again. I do, in fact, bleed back into the hip again. And he says, "Oh yeah. I thought that would happen." I was trying to have that conversation with him. But he never came by. I talked with the other doctors on the team but… he never ever came by. Of course, did he line the area like the transplant doctors did so that I wouldn't bleed into it? No. Of course I bled right back into it again.

MICHAEL: And then, just to top it off, we ended up back in other hospitals, following up on this, back in emergency rooms. Cindy's wonderful doctor at Columbia Presbyterian, Dr. Appel, had a room for her to get this dealt with in the hospital. He was upstairs. He had a room.

CINDY: He saw it and he was upset by the amount of bleeding that was happening in my hip.

MICHAEL: And we were in the ER, waiting. The ER called that surgeon again and he told them to send us home. So they sent us home and Dr. Appel was upstairs with a room for her. And he called us when we get home and he says, "Where are you?" And we're like, "They told us to go home."

CINDY: And they told him we wanted to go home.

MICHAEL: Yeah.

CINDY: I was in tears at that point. I was so angry.

MICHAEL: So anyway, Cindy recovered again. Things were good, better than ever. We even squeezed in a trip to South Africa, to see where Cindy used to have giggle-itus in her room. We went to see the room. And it was wonderful. Amazing. And then we had one final challenge and then we're done with challenges for a while, I hope. In January 2018, a new medication seemed to cause lung problems for Cindy.

CINDY: No, no, no, no. There was a fantastic drug called Rapomicin, a transplant immune-suppressant that is better for people – the survival of the transplant is much better, meaning I could hold onto it for even longer for people with APLS. So it's a great drug for me. And it helped with skin cancers. So it seemed like two of my issues would be solved with this drug. I was very excited about it and everything was going well. Then what happened? I can't remember how I got sick.

MICHAEL: You got pneumocystis.

CINDY: I know what I got. But I didn't… Ultimately, the end of the story is that that drug can cause lung problems. But usually it's in the first six months of taking it. It was not the first six months. All the other people it had caused problems with were men. But ultimately, it probably compromised my lungs and then I got pneumocystis.

MICHAEL: And that’s a very severe form of pneumonia, right?

CINDY: It's what people with AIDS would often get, and die.

MICHAEL: So the doctors thought she might not make it. We just wanted you to have one more thing to add to the near-death…

CINDY: No, I don't agree that that should go on the list.

MICHAEL: Why not?

CINDY: Because I was getting good care.

MICHAEL: But they… they…

CINDY: Oh yes. That's right. I kept running fevers.

MICHAEL: Yes.

CINDY: The fevers would never go down. Well, they would go down but they'd come right back up again.

MICHAEL: Yes, the doctors were afraid she might not make it. We get another notch for that one.

SALLY: All right, what do we call that, pneumonia?

MICHAEL: Pneumocystis. Just a tiny little detail. While I was rushing to the hospital to see Cindy – after work -- my phone rings. And it's the assisted living facility in Massachusetts where my parents were. They said my mother's health problems had gotten too great for them, and they couldn't reach any of my siblings. And I said, "I'm going to the ICU to see my wife." They said, "We're sorry to hear that. But you've got to deal with this first." So that was fun. Somehow we got through it, the way we always got through things. Actually, some people may wonder how we did get through it. And there's one key factor. Cindy – you want to tell them?

CINDY: Oh yes. Our friends have been unbelievable. And our families. I mean, it's just incredible, the amount of help we've had through the years. It's phenomenal.

MICHAEL: So many people did so much. They cooked our meals, washed our clothes, cleaned our toilets, wrote us poems, made us laugh till it hurt. One friend filled our house with flowers. They gave us extremely large amounts of money to pay for our expenses. Yeah!

SALLY: Oh my God.

MICHAEL: Donated money to us. They picked us up and drove us to doctor appointments, day after day. They traveled across the country to be with us. Our neighbors gave us the key to the most beautiful nearby apartment with a rooftop garden where we and our guests could stay. We want to mention people's names. But we're afraid – what if we left off one name by accident? It would be terrible. We would not want to insult one of these amazing people. So we just want to say, thank you.

CINDY: Yeah. Thank you! Thank you! Thank you! Thank you!

SALLY: What a story. Are you sure you weren't a couple of hypochondriacs?

CINDY: Ah, there's one.

MICHAEL: One of us definitely is.

SALLY: You are such a physical/medical miracle. Cindy – do you say to yourself, "Oh my God. What's next?"

CINDY: No. I say, "Oh my God. I can't do this ever again. I'm not going there. I never want to go to a hospital again.

MICHAEL: Except when you swallow a hearing aid battery.

SALLY: I heard about that.

CINDY: Now I’m doing old people things like, you know, getting things stuck in my ears. Swallowing a hearing aid battery. We've had to go to the ER twice.

MICHAEL: But I think we're now at the moment of truth. Because we started this episode – long, long ago – with that folder of cards and notes that I saved. At that point I was truly ready to throw out this stuff. But I think telling the story may have backfired. 'Cause now I see this as the only physical tangible reminder. Those are cards and notes that we received during the kidney transplant.

CINDY: Wait.

MICHAEL: I'm reaching over here…

CINDY: I need to actually read these because I missed out. I really was out of it between the bleed and…

MICHAEL: It's a paisley folder. And here we are. Yeah, like, look at this from a family member wishing us well and… Do you want me to shred these?

CINDY: Well, I want to read them.

MICHAEL: So I shred them later? 'Cause, you know, there might be people who want to hear the sound of a shredder.

CINDY: Yeah, I think we should shred them. I think we should keep any of the stuff you've been keeping because it's ridiculous.

MICHAEL: This is from the person who gave us so much.

CINDY: But we have the memomries.

MICHAEL: All right. I'm gonna take this one. This is from a family member. And just… this'll be… this'll be to show my good faith.

CINDY: Can I read it first? Okay, that was sweet.

MICHAEL: Okay. Here we go.

(shredder sound)

CINDY: Shred! Yay!

MICHAEL: It's a big moment

CINDY: To me, the cards don't reflect what people did for us.

SALLY: The effort.

MICHAEL: You have not looked through this folder. Many of the cards are from the people who did that stuff.

CINDY: Okay. I definitely don't want you to shred things until I read them.

MICHAEL: Well then I can shred yet. But can I shred the piece of paper that has Maryellen's name on it, which is how I met her, and then she introduced me to you?

CINDY: I don't think I can shred that.

MICHAEL: What about this treasure? One of the many mix tapes you made me, taped off the radio in 1982.

CINDY: You can throw that out.

MICHAEL: Really? All right. Can you get the trash can Cindy? Here we are. It's a very noisy metal trash can. Here we go. (clang) There. I threw it out.

CINDY: Don't come and get it again.

MICHAEL: I think it's probably thrown out for good. That hurt. But I think that we are gonna have to move on. I’m gonna go heal my wounds from the throwing out. We can't end with a tragedy. So I want to shift to a brighter note. 'Cause that's the way our story always ends. On a brighter note. In March 2020, a family in Connecticut – our very generous friends – knew that Cindy's life was at risk from Covid if we stayed in New York.

CINDY: Well, at least my kidney was at risk – which, as far as I'm concerned, is the same thing.

MICHAEL: They gave us a place to go. As many people know, they put us in this beautiful renovated barn. They might have expected us to stay for 8 days. Or 8 weeks. We stayed for 8 months. And I feel this saved Cindy's life.

CINDY: Yes. I feel like it was critical to not getting Covid, and the repercussions from Covid could be pretty awful. I'm old and I'm immune-suppressed, and that didn’t bode well for people.

MICHAEL: But, as you said, while we lived in the barn, we were afraid to go to your usual doctor appointments. So we didn't go. And we worried what would happen if you didn't go to doctors. But actually, with the isolation, you got no infections, no illness, and life was kind of… normal.

CINDY: And if you don't go to doctors, you don't know if anything's wrong…

SALLY: Like what you don't know can't hurt you.

CINDY: Yeah. Exactly.

MICHAEL: Now we've moved our quarantine somewhere else and your health's been pretty darn good.

CINDY: Yeah. It's fantastic.

MICHAEL: For two years. Have you ever felt good for two years in a row?

CINDY: I don't know.

MICHAEL: And we can see from all the beautiful art that Cindy has created during this time. cindyruskin.com is where you can see it. That's cindyruskin.com. And it is really a wonderful testament to what Cindy can do when she feels well.

SALLY: Yay!

CINDY: Well, I have to say, I know I wouldn't have survived without Michael. Because there were so many times where… In fact, my doctors even said to Michael, "If she says she doesn't want to come in, bring her in." I didn't want to go in when I was too tired and too sick to go in. And I wouldn't have gone in. And those times that I got help, Michael was my advocate every step of the way. Absolutely essential. The people I knew who died first were single and I feel like having a partner is critical for medical survival.

SALLY: And Michael doesn't miss a detail.

CINDY: No, as one of my cousins said, "It's better to have the…" -- I was going to say "neurotic" but that may not be the right word – "the pessimist to be the caretaker because the optimist would definitely ignore the symptoms."

SALLY: Yeah.

CINDY: So Michael lists more brushes with death than I do because he's the pessimist.

SALLY: We're up to 10.

MICHAEL: Wow. So it's 10 brushes with death.

CINDY: What are you doing? Tempting fate here?

MICHAEL: I hope not. Are we superstitious?

CINDY: No.

SALLY: Okay. Ten is counting Covid and Cindy staying isolated.

MICHAEL: Okay, we'll make it 9 then.

CINDY: No, that's 9.

MICHAEL: We'll make it 9. For my part, I've got to take a deep breath because I want to do something that Cindy thinks I don't do enough. I don't know if I ever told you this, Cindy. But at one point, when our bodies were giving us a lot of trouble – in different ways, I used to imagine us without human bodies…

CINDY: I can't believe you never told me this. You tell me everything.

MICHAEL: And the way I saw it is that we were like two comets looping back and forth in the sky, leaving a trail of sparks behind us.

CINDY: Of glitter!

MICHAEL: And we were up there, exploring the universe the way we explored Boston and San Francisco and New York and Cape Town. And now, I don't have to think that way. Because when I'm here working with Sally on the podcast and you're in the other room working on your paintings, it seems that all those near-brushes with death – all the pain, all the challenges – are behind us. At least for a while. And we can lead a happy healthy life. Are you up for that Cindy?

CINDY: Of course. As long as you're there. You're not allowed to go first.

MICHAEL: Okay. Let's give it a whirl.

CINDY: Is the episode over now?

MICHAEL: We're done.

CINDY: Oh good. Because I need to go wee. Your kidney is really working well.

MICHAEL: Well, enjoy it. It's yours now.

----------------

CINDY: Okay, before we go, I want to thank the superb medical teams at the three hospitals where I received my kidney transplants. First, at Tufts University Medical Center in Boston, then at UCSF Medical Center in California, at the last one at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City. And speaking of those places I want to add a very special thanks for people who did so much to keep me alive and take care of me. Dr. Jordan Cohen at Tufts. Gloria Horns and all the doctors on the transplant team at UCSF. And Dr. Gerald Appel at Columbia Presbyterian who has saved my life many times.

MICHAEL: And last, but definitely not least, we'd both like to thank Virginia Fink, our wonderful therapist, who not only carried Cindy out of an appointment but also truly helped us to be together today.

CINDY: Woo hoo, Virginia!

MICHAEL: Yay, Virginia! If you want to provide financial support to any of the three transplant units that helped Cindy, we've added donation links on our website. While we're at it, we also added donation links to some of the organizations that help with dialysis patients, kidney donation and lupus research. You'll find the links all at throwitoutpodcast.com. One last reminder: It is extremely easy to sign up to be an organ donor after your death. Please don't wait. Sign up now at: organdonor.gov. And Sally, what do you want to say?

SALLY: I want to remind our listeners that you can get reminders about new episodes by following us on Twitter and Instagram at throwitoutpod. And if you go to Apple Podcasts and give us a rating, we'd do almost anything to thank you – except give you a kidney. One last news flash: Our excellent friend Tim AND the Very Famous Nancy BOTH admit that they hum our theme song while doing weekend chores. So if you join the chorus, you'll be in very good company until the next episode of…

MICHAEL: I couldn't throw it out!

CINDY: Wooo!

THEME SONG: I Couldn't Throw It Out

Performed by Don Rauf, Boots Kamp, and Jen Ayers

Music by Boots Kamp and Don Rauf

Lyrics by Don Rauf and Michael Small

Out here in Nancy's – her big garage

This isn't a mi- This isn't a mirage

Decades of stories, memories stacked

There is a redolence of some irrelevant facts.

But I couldn't throw it out

I have to scream and shout

It all seems so unjust

But still I know I must

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Well, I couldn't throw it out

I couldn't throw it out

I'll sort through my possessions

In these painful sessions

I guess this is what it's about

The poems, cards and papers

The moldy musty vapors

I just gotta sort it out.

Well I couldn't throw it out

I couldn't throw it out

I couldn't throw it out

I couldn't throw it out

END OF EPISODE 10

Cindy Ruskin

Artist

Cindy Ruskin is a self-taught oil painter and mixed media artist. Originally from South Africa, she received her BA in Fine Arts (Art History) from Harvard. Cindy lived in New York for more than 20 years where she devoted herself to community art projects including the creation of a large mosaic for the Lower Eastside Girls Club; she also ran the art program at Avenues for Justice, an alternative-to-prison organization for juvenile offenders. In the past year Cindy’s paintings were selected for eight magazines including All SHE Makes, Clover and Bee, Goddess Art, Photo Trouvee, and The Purposeful Mayonnaise. She exhibited her work at the PxP online Gallery, and this year her work was selected for in the online group shows “Lavish” at the TMP Gallery, “Shades of Blue” Awards Show at the Camelback Gallery, and “Home” with the Arts to Hearts Project. To see Cindy's art, go to: cindyruskin.com