2Pac's 1991 Interview: Kindness and Rage

Tupac Shakur talks about his violent arrest for jaywalking; his Black Panther family; Hollywood hypocrisy; and his program for poor urban kids. Plus, special guests discuss his contradictions (explicit)

Notes for I Couldn't Throw It Out, Season 2, Episode 17

Tupac Shakur: My 1991 Interview

Note: This episode was updated on 2/17/24 to correct an inaccurate detail about 2Pac's death that was pointed out by listeners.

Media guide:

For our list of the best music, movies, TV, websites, podcasts and books about Tupac, click here.

Show notes:

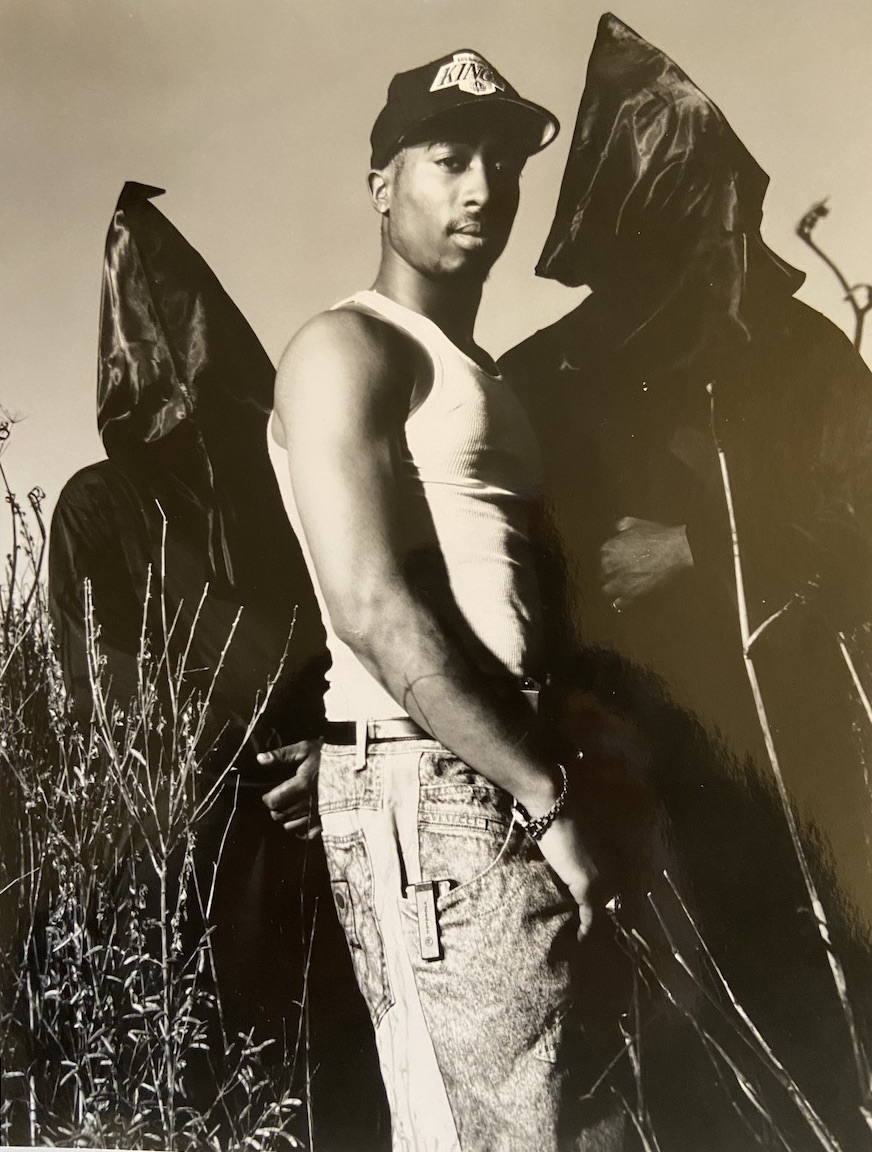

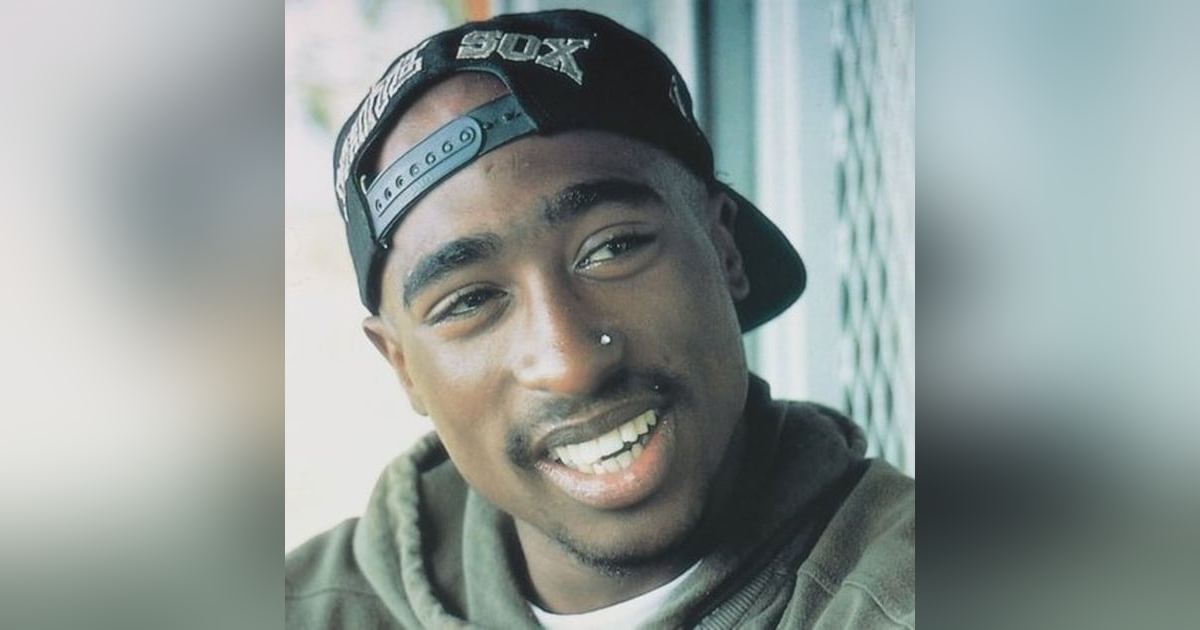

In 1991, I was way behind with the deadlines for my book about rap music, Break It Down: The Inside Story from the New Leaders of Rap. That's when I got a call from a publicist, telling me I'd regret it if I didn't include 2Pac -- who had just released his first solo album, 2Pacalypse Now. She sent me this promotional photo for the album, which I reprinted in my book and saved for 32 years.

Because our interview was last minute -- and there were no lyrics sheets with his just-released album -- I asked Tupac to share lyrics from his song "Trapped," which he wrote in 1990 about police brutality. The words predicted the future in an eerie way. Tupac told me about his own arrest for jaywalking in Oakland California a few months before we spoke. His experience precisely aligned with the lyrics of the song he wrote a year earlier.

In case you want to hear the official version of "Trapped," you can watch it on Youtube:

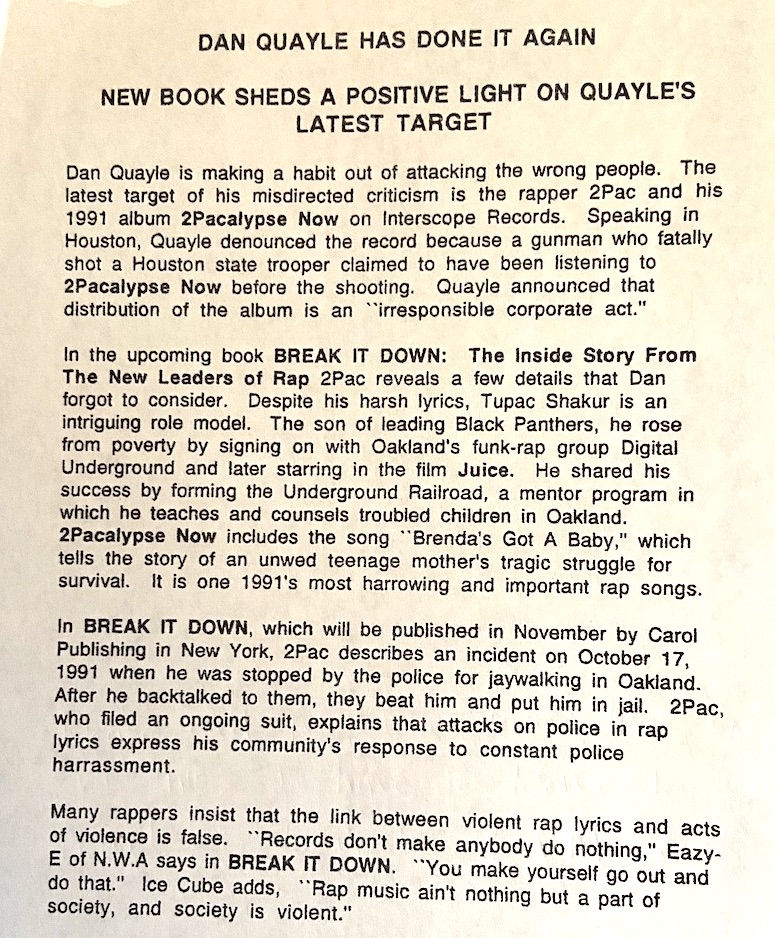

A year later, when my book was released, Dan Quayle was grandstanding before the 1992 November presidential election, claiming that 2Pac's album had incited a Houston gunman to shoot a police officer. So I created this press release for my book:

I don't think I got any press coverage for that. Which is probably a good thing -- because I would have been inflating a non-story. Sometime later, it was discovered that the shooter had not been listening to 2Pacalypse Now. But it still serves as a reminder of how politicians use and abuse hip-hop for their own purposes.

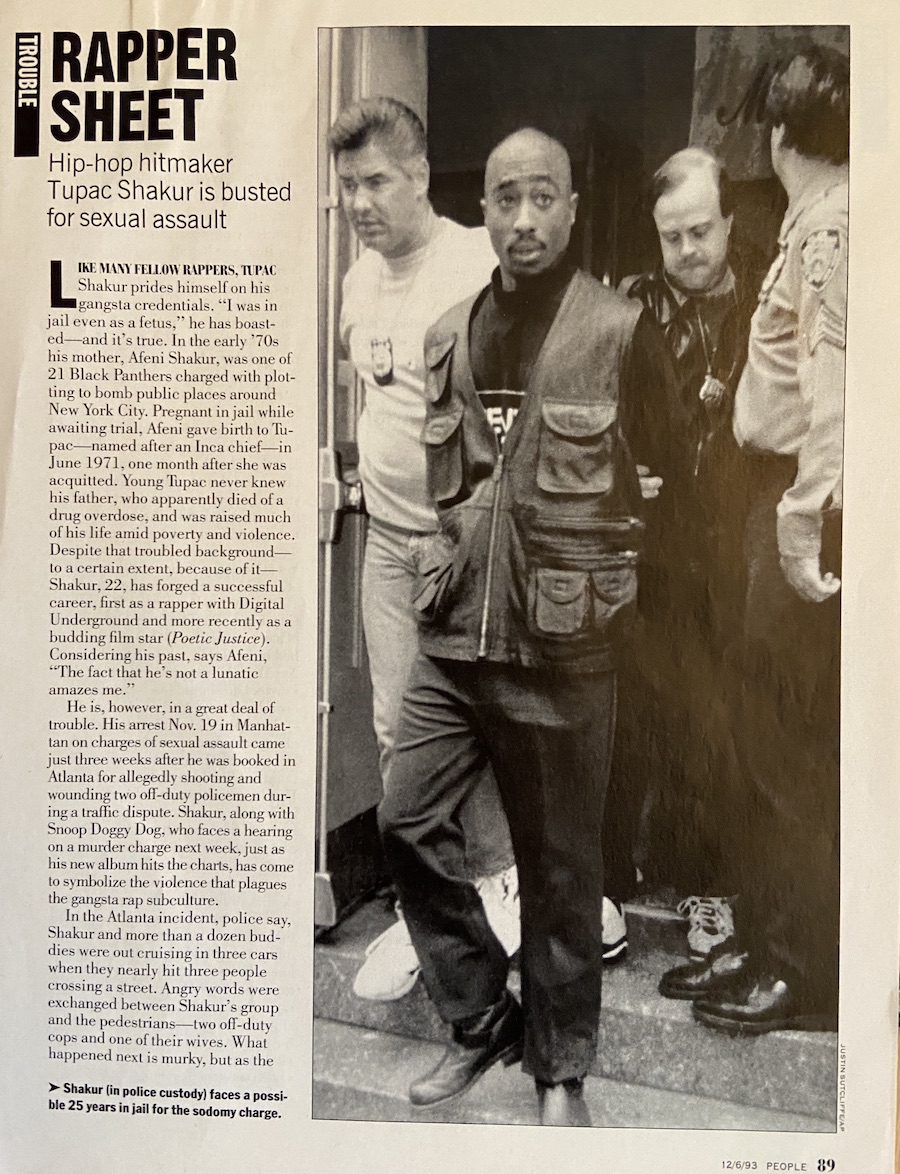

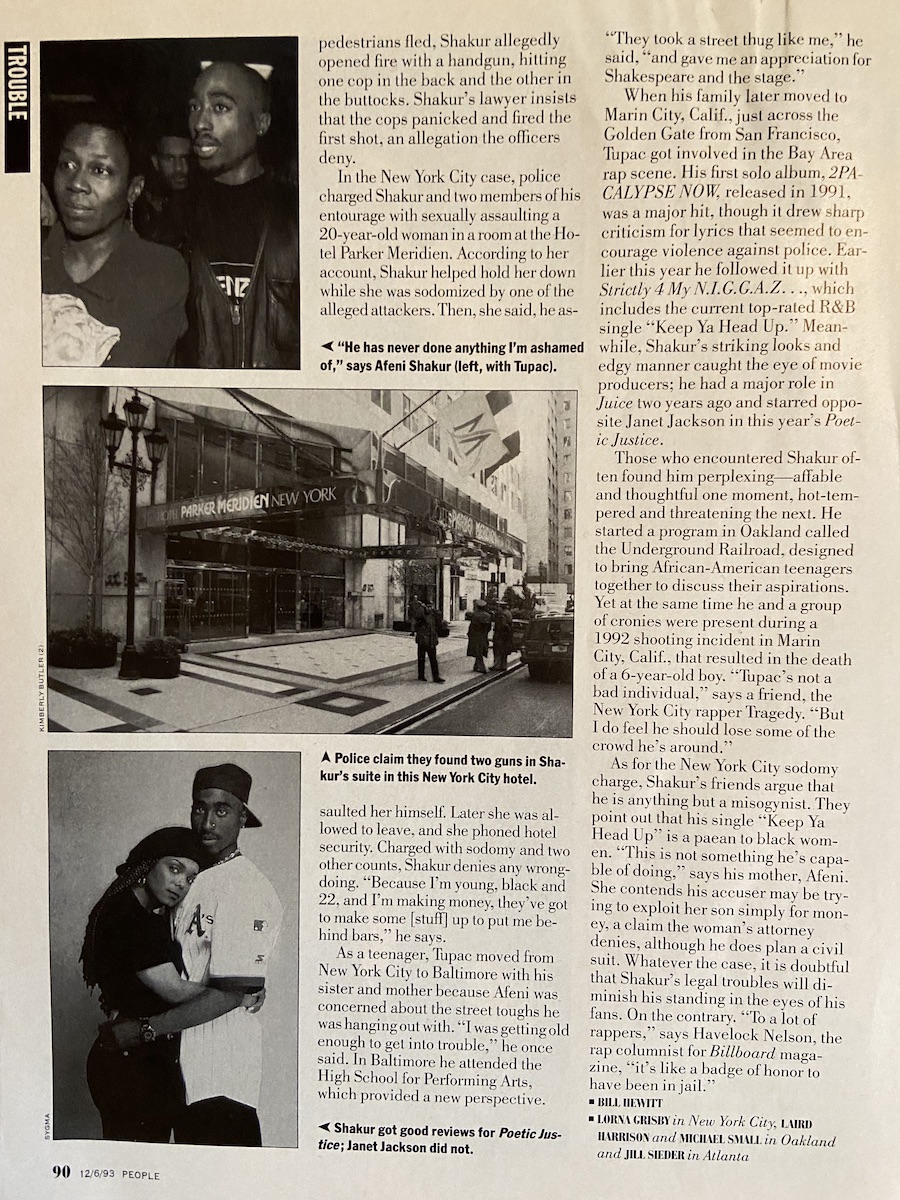

In 1993, Tupac was arrested for sexual assault -- which he strongly denied, even after he had to serve a jail sentence for it in 1995. People Magazine invited me to help with the reporting on the story and I still have all my notes.

Here's the summary I sent to them for background:

2Pac is an extremely confusing person. He is well-spoken, lucid, likable and convincing at one moment, and he's a rash dangerous hothead a few minutes later. His flip-flop personality probably comes out of the contradictions of his past. He is proud that his parents were Black Panthers and also takes pride in his innate artistic talents that were developed at Baltimore's School for the Arts. Yet his past also included crushing impediments: poverty, homelessness an unfinished high school education and a father who died of a drug overdose.

Outsiders might find it difficult to understand 2Pac's odd kind of integrity, which might have contributed to his current problems. He seems to feel that it is his responsibility to use his power as a rapper to make the world hear what life is like in poor urban neighborhoods. Because it is so important for him to be known as an authentic voice, and not an entertaining faker, he refuses to put a safe distance between himself and the world he describes. Other rappers move on, but 2Pac surrounds himself with troubled, angry, dangerous young men.

I was really happy to see that People's reporting was more balanced and thoughtful than what I saw elsewhere. Of course, I saved the article. Here it is:

I never expected that I'd be called on to cover 2Pac's death. But in 1996, when I was the arts editor at Wired Magazine's HotWired site, I posted a tribute to him. Though HotWired site was removed from the Internet years later (presumably for legal reasons), I saved a copy of that article. Here's the beginning and the end...

After Tupac Shakur's death last Friday, my friends started asking me questions. Did I know the inside details? Who killed him? Was it gang related? Was he really a bad guy? Did he deserve it?

In a way, those questions make me angry - partly because I had such a tough time getting anyone to listen to me talk about Tupac five years ago. At that time, rap was being blamed for creating all the violence in human history, and I was trying to counteract that hype with a story about Tupac's positive qualities. Not only had he written a sympathetic rap about unmarried mothers ("Brenda's Got a Baby") but he was planning a mentor program to help poor kids in his Oakland neighborhood. I had a strong positive angle. Nobody wanted it.

As other rappers have learned -- to their financial gain and often to their personal harm - violence is the best way for a rapper to get attention. Tupac surely proved this more than once....

For me, the saddest thing about Tupac's death is that it shows just how little hope he had for the future. He had wealth and lots of talent but he didn't see where he could go in this world without the gangsta persona. He couldn't picture himself in a safe place. He couldn't imagine a world where he could find peace by taming his temper and creating his Underground Railroad. Instead, he died, and now everyone's asking about him.

And now, a little more about the two guests who shared insights about Tupac on this episode:

Dr. Dre - who was the co-host of the hugely influential TV show Yo! MTV Raps Today from 1989 to 1995 -- made a return visit to the podcast, after sharing his wisdom with us on a previous episode about N.W.A.'s Eazy-E.

Despite his challenges from severe diabetes that caused him to lose his sight in 2019 and then have a leg amputated, Dre is still energetically and optimistically dedicated to spreading the word about hip-hop and helping others. He's putting final touches on his memoir Yo! Bigga Stuff: The Dr. Dre Episodes -- which will include details about helping to launch the careers of major rappers, along with his insights about hip-hop culture. He is now fundraising for the Parawhirl Streaming Network, a collaboration with the American Basketball Association that will give easier access to streaming media for people who are blind, deaf, autistic, or have other challenges. To reach out to him about Parawhirl, use the form here. (And yes, for those who don't know, there are two hip-hop stars with the name Dr. Dre. This Dr. Dre had his moniker before the other Dr. Dre -- the rap producer and Beats headphone magnate -- rose to fame.)

April Beezer, who first crossed paths with me as a student in my writing class at the alternative-to-prison program Avenues for Justice, is a recent graduate of New York City's Guttman Community College. While she's in training programs for her ultimate career, she has been recording rap songs at Believe Music Studios in the Bronx. The studio was founded by Kenny Cooper, who also graduated from my writing class. Part of the studio's mission is to help kids from inner city neighbors to express their creativity in a positive way.

Here are a couple of the songs April recorded, using the name AB Hoodrich:

Related links:

Our media guide:

Movies, TV, music, websites, books and more about Tupac

Our two podcast episodes about NWA's Eazy-E:

My 1991 interview with Eazy-E

My tour of Compton with Eazy-E during the 1992 L.A. riots

Listen and rate us: Apple Podcasts

Follow: Instagram (@throwitoutpod)

Will anything get tossed? Could happen. THANK YOU for listening!

I Couldn't Throw It out

Season 2, Episode 17 - 2Pac's 1991 Interview: Kindness and Rage

Michael Small:

In November 1991, I interviewed the rapper Tupac Shakur. He told me about being arrested a few months earlier in Oakland, California, for jaywalking. Here's what he said:

Tupac Shakur:

I ended up saying, "Well, fuck y'all, give me my citation and let me be." As soon as I said "fuck y'all," they grabbed me, slammed me, put me in a chokehold, banged my face against the concrete, and I was unconscious. I woke up, cuffed up, with my face in the gutter, with a gang of people watching me, like I was the criminal.

Michael Small:

To hear everything Tupac told me, keep listening to this episode of I Couldn't Throw It Out.

[song excerpt starts]

I couldn't throw it out

I had to scream and shout

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

Before I turn to dust

I've got to throw it out

[song excerpt ends]

Michael Small:

Hello, Sally Libby.

Sally Libby:

Hello, Michael Small.

Michael Small:

I have some things here that I saved for 32 years. And these things actually relate to one of the biggest news stories of 2023. Now that is not what you expected, is it?

Sally Libby:

Not at all.

Michael Small:

Just for the record, Sally, what is that news story?

Michael Small:

Well, the news story is about Tupac Shakur. In late September, twenty-seven years after Tupac's murder, Duane Keith Davis was arrested in Las Vegas in connection with the fatal shooting of Shakur in 1996.

Michael Small:

Here's what I found in my boxes that relates to all of this. It's an audio tape of a pretty long phone interview I had with Tupac in 1991 when he was 20 years old. And this is one of the very first interviews of his solo career. No one had heard this tape, except me, until I sent it to you, Sally. And since you're the first listener, what was your reaction?

Sally Libby:

I thought, you lucky dog. I would have loved to have been in your position at the time. I thought he was so articulate and so mature and to have formed a worldview at 20 is pretty amazing.

Michael Small:

That really is a tempting way to tell people that we will be playing that whole interview later in this episode and will share the rest of my reporting about Tupac and we'll decide if I can throw any of it out. But before that, there's someone else with us today who has been quietly lurking till I introduced her. She's been a friend of mine for about nine years. She's about 42 years younger than we are. She's coming at rap music and Tupac from a really different perspective. I feel so lucky that she agreed to join us today. Sally, please welcome April Beezer.

Sally Libby:

Welcome, April. So glad you're here.

April Beezer:

Hello. Thank you for having me.

Michael Small:

Do you want to give Sally an idea of how we met?

April Beezer:

We met through an alternative to a incarceration program named Avenues for Justice. I was like 15, and I was in the program. And Michael was helping me with a speech for the gala. And then after that, he started tutoring me. He helped me get into college and finish high school. And then he just helps me with life now.

Michael Small:

April helps me with life too, believe me. Yes. One thing that didn't get mentioned is on the side, April recorded rap songs and I love them.

April Beezer:

Thank you.

Michael Small:

I think that is one way to show that you know way more than Sally and I do about what's happening in the rap world now.

Sally Libby:

Right.

Michael Small:

And we want to hear your perspective.

April Beezer:

No problem.

Michael Small:

To get started, can you explain to other people what you think is so special about Tupac's music?

April Beezer:

I honestly feel like Tupac's music was special because he was the voice for the voiceless. And I say that because his music spoke for the minorities. He was sending a message, basically, pleading for social change. And he did it through music.

Michael Small:

Do you think that in a way he did that better than most other rappers?

April Beezer:

He did because he was involved. Like his parents was the Black Panthers. So he seen, like, the political side. And then, like, when he went to jail, he seen the system. He seen all sides of this. So he was able to speak from all perspectives.

Michael Small:

What about his beats? Did you see any change from the beginning till later? Did he develop in that way?

April Beezer:

He used a flow and he used unique words to tell a story. So he put it all together and, like, he created a masterpiece.

Michael Small:

Is there a reason why people kind of go crazy for him?

April Beezer:

I feel like it's his style, the type of person he was, or the type of person he showed himself to be. A lot of people admired that.

Michael Small:

But it's a little confusing because on the one hand, he had lyrics that are really thoughtful and show new sides of our culture that people hadn't heard about. And on the other side, he has lyrics, some of which are really pretty violent and very nasty. How do you explain that contradiction?

April Beezer:

I feel like he was giving you the best of both worlds. He wasn't trying to show you one thing and hide the other thing. He was trying to show you both things so you could see it from both sides.

Michael Small:

I wonder if you have any thoughts about why they couldn't arrest anyone for his death until now?

April Beezer:

A lot of the reasons why they couldn't arrest anybody for it. One, because the person that was robbed, like, at the start of the situation, he died. So they couldn't arrest him. And also, nobody wanted to really snitch because you know what they say, "Snitches get stitches." And the people that was there, they don't want to speak up. So it's like the case will be forever unsolved. The most they could do is get the people that did talk.

Michael Small:

That makes it challenging to solve a murder.

April Beezer:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

We never would have had that perspective without you. Sally and I both did some research about this and we were blown away, not just by his accomplishments, but also his popularity. I would say this is one case when you can literally say he was off the charts.

April Beezer:

Yes.

Michael Small:

Sally, could you share some of what you found out about how popular he was?

Sally Libby:

Sure. He had 10 platinum albums.

Michael Small:

What were the total album sales?

Sally Libby:

75 million albums worldwide.

Michael Small:

So we gotta stop on that for a minute, because a total of 75 million albums is just so huge. And when you're talking about albums, you're talking about pre-2011, really, when Spotify came out. Because now it's all about streaming. The numbers for streaming are at a whole different level. A few months before he died, 2Pac released "Hit 'Em Up," which was one of his most popular songs. April, you want to give a guess of how many views it has on YouTube?

April Beezer:

I know it's over a million.

Michael Small:

Okay. On YouTube, that one song video has 654 million views.

Sally Libby:

Whoa.

Michael Small:

On Spotify, that song -- we're talking one song -- had 507 million streams. If you put those together, that is more than a billion streams, just YouTube and Spotify. For one song. Some of his other songs, like California Love, have even more on Spotify.

Sally Libby:

If I could just remind everyone, the years he was active was 1989 to 96. That's it.

Michael Small:

April, does that surprise you or not?

April Beezer:

Yeah, that does surprise me. It surprised me how in such a short bit of time he became worldwide so fast.

Sally Libby:

I have a few more statistics. In 2002, he was inducted into the Hip Hop Hall of Fame. In 2017, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Rolling Stone listed him as 86 out of 100 most influential musicians of all time.

Michael Small:

Wow, I thought he'd be higher.

Sally Libby:

One more thing. I didn't know this. He was in six movies and in 2023, he was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Michael Small:

I'm going to move towards the literary side for a minute. The first authorized biography of Tupac is out this month. It's by Stacy Robinson, who knew Tupac when they were in high school in Marin City, California. But this is definitely not the first book that Tupac inspired. Conservatively, more than 40 books have been written about him, including one called "What Pac Says: Tupac Shakur Speaks from the Other Side." This was written by a medium named Christine Carlson, who says that Tupac dictated the book to her after his death. Then there are two major documentaries about his life and his death, one of which was nominated for an Oscar. And there's a fictional movie based on his life called "All Eyez on Me." Then there's a five-part TV series called "Dear Mama" about his relationship with his mother. It was on FX, but it came out on Hulu this year. And it is great. Definitely worth watching if you want to learn about Tupac. One other thing about Tupac relating to literature. If you search the internet, you can find many lists of the books he read. The books he read included" The Tibetan Book of the Dead, 100 Years of Solitude, Moby Dick, 1984, Native Son, The Grapes of Wrath, Tropic of Cancer, and a key one, The Prince by Machiavelli. That must have been a favorite because he later used the stage name.

April Beezer:

Makaveli. He went to, I think, a theater school.

Sally Libby:

Yes, in Baltimore.

Michael Small:

One more question for you, April. He had the chance to use that education to break out of a world of gangs and violence and all that, and he still returned to that world. Can you help explain why?

April Beezer:

You could take the person out of the 'hood, but you can't take the 'hood out the person. The people that was around him, that influenced him. So he just had a lot of negative influences impacting how it turned out.

Michael Small:

If you look at the troubles in his adult life, there's his 1993 arrest in Atlanta that was for shooting two off-duty police officers. There was an arrest the same year for sexual assault that led to a prison sentence in 1995. There was an alleged assault of the director of the movie "Menace to Society" that led to 15 days in jail in 1994. And then there was a wrongful death suit in 1995, when a six-year-old was killed by a stray bullet after one of Tupac's concerts. Is there really a best side to that world? It seems pretty negative.

April Beezer:

It all depends on how that person sees it and what they get out of it. Some people see good and negative because sometimes you can get good out of a negative. It all depends on the mindset. And I feel like Tupac was a pretty positive person. When he thought about negative things, that he found the way to make it sound good.

Michael Small:

Do you think that if he had not made rap songs about his battles and with threats in them that he might still be alive?

April Beezer:

Honestly, it's hard. Just because he made like the raps and everything, that was just showing like what he wanted to show. But behind the scenes, we never knew what he really did. It all depends.

Michael Small:

We don't know if it was all an act. Or if he was actually involved in things.

April Beezer:

Yeah, we don't know. You know, some people say he did this to cover themselves. So we don't know what really happened. Because nobody wants to speak up. And when they do speak up, they say very little.

Michael Small:

This leads up to the story about 2Pac's death. It's really complicated and people have been disagreeing for years about the details. But here's what came out of testimony at a court case in Las Vegas: The problem started in 1996 at a California mall with a fight over a chain. It seems as if the chain belonged to someone affiliated with 2Pac. Later on, when 2Pac and his crowd were in Las Vegas for the Mike Tyson fight, they ran into someone they thought was involved with the chain incident. So they retaliated by attacking him. But then he wanted revenge against Tupac. So he got help from his uncle Duane Keefe Davis. He's the one who was arrested this year for his role in 2Pac's murder. What we know is that they got in a car with two other people, and someone in that car shot 2Pac. And it's all so crazy because it started with a fight about a chain. April – how can people end up attacking each other and killing each other because of a chain?

April Beezer:

Because they feel like it's a principle. They see it as a sign of disrespect. And a lot of gang members are like... people in general don't take disrespect lightly. So they saying it will be like, "You live by the gun, you die by the gun." So that's basically what happened there.

Michael Small:

It's so weird. You and I have talked about that a lot over the years, how disrespect has become dangerous. It's so easy for me to say, but in the world where I grew up, if you disrespected me, I just made a joke about it and went on.

Sally Libby:

Right.

Michael Small:

I got disrespected. All the time.

Sally Libby:

By me, especially.

Michael Small:

How does it become that disrespect is more important than a life?

April Beezer:

I feel like some people feel like they have something to prove. Yeah, like it's they pride, their ego. Like they feel like they have something to prove, especially like if you have gang ties. With your gang here, you get disrespected and you don't do nuthin' about it, they're going to consider you as pussy or a punk or whatever word they call it. So like they basically showing themselves that they tough pretty much, like they're about it.

Sally Libby:

There's no turning the other cheek in that world, right?

April Beezer:

Yeah, it's an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, yeah.

Michael Small:

You said something just then that for the first time in my life helped me understand something -- which is that the one thing they have is their pride. And if you take away the one thing they have, that's serious.

April Beezer:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

Wow. It would be great for some people who didn't listen that carefully or who haven't heard his lyrics... I was hoping, April, there were a couple songs that maybe you could just read a little excerpt from them. I asked you what your favorite song is, which is?

April Beezer:

"Keep Ya Head Up"

Michael Small:

Yeah, and why is that one of your favorites?

April Beezer:

It's really a good song. People in my community, we can relate to this. It's encouraging. It's for empowerment. If you're having a bad life, like keep your head up.

Michael Small:

Can you read us a little excerpt from the song?

April Beezer:

Okay.

(Reading)

You know what makes me unhappy?

When brothers make babies and leave a young mother to be a pappy

And since we all came from a woman

Got our name from a woman and our game from a woman

I wonder why we take from our woman, why we rape our woman.

Do we hate our woman?

I think it's time to kill for our woman.

Time to hail our women, be real to our women.

And if we don't

We'll have a race of babies

That will hate the ladies that make the babies.

And since a man can't make one

he has no right to tell a woman when and where to create one.

So will the real men get up?

I know you're fed up ladies, but keep ya head up.

Sally Libby:

That's great.

Michael Small:

There are not a lot of songs of any kind with that kind of powerful message supporting women. And especially, I think April, from what you're saying, it's supporting women from the perspective of a particular world. Does that make sense?

April Beezer:

Yeah.

Sally Libby:

But now as a contradiction, didn't he have to go to prison for sexual abuse?

Michael Small:

That was in 1995.

April Beezer:

Yeah. He strongly denies those allegations though.

Michael Small:

And Suge Knight bailed him out for $1.4 million.

Sally Libby:

$1.4 million?

Michael Small:

Yes. And that's how Tupac ended up on Death Row Records, and it was Snoop Dogg who encouraged Suge to do that.

April Beezer:

Yeah, because he was a really good artist. Like who would want to lose him as an artist? Like that's so much money being lost.

Michael Small:

Well also talent being lost.

April Beezer:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

So that brings us to a song that he created just a few months before he died, and it's called "Hit 'Em Up." And it's really different in that it is violent and threatening. When you watch the video, it looks a lot more fun than when you just listen to it or just read the lyrics. It's more aggressive when you just see the lyrics. April, can you read us a little bit of "Hit 'Em Up?"

April Beezer

(Reading)

All of y'all motherfuckers, fuck you.

Die slow, motherfucker.

My four-four, make sure all your kids don't grow.

You motherfuckers can't be us or see us.

We motherfucking thug-like riders

West Side till we die.

Out here in California, n---, we warned ya

Michael Small:

To me it would seem so extreme that it almost feels like not a joke but...

April Beezer:

I feel like he was trying to show more aggression. Basically trying to show that he's ready for anything. He knows what it comes with and he's prepared.

Michael Small:

You're taking it more seriously. I thought it was sort of like acting, drama.

April Beezer:

No he's serious in this song. He's talking about hitting somebody up with a 4-4.

Michael Small:

Well he was angry because he was shot earlier, and he thought it was Biggie who put people up to it. This is aimed at Biggie Smalls, isn't it?

April Beezer:

I wouldn't say directly to Biggie Smalls, but I would say it's directed to the East Coast. Okay. And Biggie's crew too, right? Yes, which is the East Coast, yes.

Michael Small:

Sally, I think this is a good time to share the recording that we made earlier this week in another conversation about Tupac. That's when we asked for some guidance from someone who is always an excellent source of information about hip-hop culture. His name is Dr. Dre. And just to be clear, there are two famous Dr. Dre's. This Dr. Dre is best known as the co-host of the early 1990s TV show Yo MTV Raps Today. On that show, he and his co-host Ed Lover helped to kick off the career of many famous rappers, which is why we really wanted his perspective on Tupac. Here's what we learned.

[Dr. Dre interview begins]

Michael Small:

Dre, we are so happy to be speaking with you again.

Dr. Dre:

Thank you, thank you.

Michael Small:

First of all, did you ever meet Tupac?

Dr. Dre:

Quite a few times.

Sally Libby:

Did he feel, did it feel like he had a big presence?

Dr. Dre:

With Tupac, he had just a certain glimmer and a gleam. Because he was a talented lyricist. He was a very profound personality. But he was a very attractive man to so many women and to so many men. And what came out of his mouth brought people in. What he did brought people in.

Sally Libby:

Right, how about the ego?

Dr. Dre:

Ego was always there. I believe he always knew who he was, but it was just a matter of him getting an opportunity and a stage and the rest was history.

Michael Small:

I am particularly interested in the contradictions within Tupac.

Dr. Dre:

Look. Tupac was educated, but he also was braggadocious, which is what rap music was. But he also was loving and caring. He wasn't all malicious and all pound my chest, I'm the only one.

Michael Small:

I found it confusing.

Dr. Dre:

Who isn't confusing?

Sally Libby:

That's right. Every one of us have contradictions.

Dr. Dre:

Exactly, tell me someone right now who didn't live with a certain sense of confusion. So yes, Tupac had a lot of contradictions. And he lived the way he wished to live. Was it always correct? Can't say that. He had a lot of hypocrisy, but at that moment in time, he was saying, "I'm gonna give it my best shot, because I may not get another shot at all."

Michael Small:

It's interesting, because even when I was speaking with him, he went from one minute being incredibly thoughtful and insightful, and then when something got him angry, he was ready to talk about getting out guns. Immediately, like, I'm going to go shoot, I'm going to kill.

Dr. Dre:

Would Tupac speak about guns, acting and reacting to that? Absolutely. Because that was his experience. That was what he understood. You know, when you live from day to day, not knowing whether you're going to be up, down, sideways, or in the middle, your reactions and your speech patterns and your discussions are much different than someone who can sit in a single place and make a different decision. So I can't judge why he did things that he did, or he reacted his way. Because I didn't grow up with him and I wasn't educated with him. But I can respect the fact that he was who he was.

Michael Small:

Did you hear about the TV series Dear Mama?

Dr. Dre:

Yes, I did.

Michael Small:

There was one part in that where they showed him at the Baltimore School of the Arts, and he seemed like not a gangster. He seemed like a kid who was getting a lot and...

Dr. Dre:

He wasn't a gangster. See, this is where our confusions happen, because it's a misnomer. Is Sylvester Stallone actually Rambo? When this was going on and rap music was starting to emerge as the music of the world, at his time and where he was coming from, being a gangster rapper was that thing that, you know, gave him a sense of security. Gave him a sense of, you know, "I can do this." It's easy for us now to look back and say, "Hey man, why were you doing this? What was that about?" Then when you're in the middle of it and in the heat of it, your decision making is totally different. Fortunately, we experienced all of Tupac. Does that make him bad or good? Or does that make him just human? I'll go with the human part of it because I don't hold anything against him.

Michael Small:

What was most important about what he contributed?

Dr. Dre:

Can't judge that at this point. Because we didn't get the opportunity to see that to its fulfillment. It was taken away. He didn't finish what we thought he was gonna do. So saying what his contributions were, six movies, many successful albums... What he did resonated with so many different people. Because people still speak of him like he's here. Millions and millions and millions of people love him. No matter how he left, what he did, and how he did it, he made his point. All praises due. In one of our conversations, I said, I understand what you're doing with Thug Life. But why are you yelling fire in a crowded theater? That doesn't ever work out well for anybody. And he was like, "No, I'm just trying to get attention on what we need to do." And I said, "That's great. But be careful when you're screaming fire, because everyone doesn't take it the same way. When you have a legion of people now following you. But unfortunately, his demise was... I don't even say just a tragedy... But remember that we all have to be careful of our actions and our words because there's consequences to that. And I'm not here to judge or pass judgment. So I can only throw out love, peace, blessings, and say, I hope whatever his spirit lies, it's with a smile and the hope and compassion of greater prospects.

Michael Small:

And that's the word on Tupac from Dr. Dre, which means that we are ready to hear my full interview with Tupac. It's one of the last interviews I did for my book about rap music. That's why it was on the phone and not in person. And I nearly decided not to do it.

Sally Libby:

Why did you almost not talk to him?

Michael Small:

Tupac was almost unknown back then. He had been a dancer and a roadie and a rapper with the group Digital Underground. But I don't think I even had a copy of his first album, 2Pacalypse Now, because it had just come out a few days earlier. And his first movie, which was Juice, had finished filming. But it wasn't out yet. So when I got a call from a publicist who said, "'This guy is amazing, you have to talk with him," I almost said, "No, I don't think so."

Sally Libby:

Never say "No, I don't think so." Never, never, never.

Michael Small:

What convinced me- is that a few months earlier, he had a run-in with the Oakland police. This was several months before Rodney King and the LA riots. And it was years before Eric Garner, Michael Brown, George Floyd. So Tupac was actually the first person to make me aware of what it was like for a young black man to be in an encounter with the police. He had a song called "Trapped". And that was all about a young man's encounter with the police. So I started the interview by asking Tupac to recite it for me. By the way, we had terrible tools for taping phone calls back then. So the audio quality is not ideal. And just in case you miss any parts of it, we're posting a transcript on our website, throwitoutpodcast.com. Anyway, here's my interview with Tupac.

[1991 Tupac Shakur interview begins]

Michael Small:

Can you give me some lines from "Trapped" that sort of apply to the whole situation with the police?

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah.

(Reciting)

They got me trapped

Could barely walk the city streets without a cop harassing me

Searching me

Then asking my identity

Hands up

Throw me up against the wall

Didn't do a thing at all

Telling you one day these suckas gotta fall

Cuffed up...

(Correcting himself)

No...

(Reciting again)

Bang bang.

(Correcting himself)

No.

(Reciting again)

Cuffed up, throw me on the concrete

Coppers tried to kill me

But they didn't know this was the wrong street

Bang bang

Count another casualty

But it's a cop who shot this

Who do you blame?

It's a shame because the man slain

He got caught in the chains of his own gang

Michael Small:

I listen to that and I go, "Isn't that like an almost exact explanation of what happened to you?"

Tupac Shakur:

That is exactly what happened.

Michael Small:

Now when did you write the song?

Tupac Shakur:

A year ago. The beginning of 1990, yeah.

Michael Small:

At that time, had anything like that ever happened to you?

Tupac Shakur:

Not of that magnitude. Just like a little bit. You know, like harassment, vocals. Like, you know, "Get the fuck off the streets, n---s. Get off the streets." You know, "Don't stand in the corner, go make some money, stop being porch monkeys!" And shit like that.

Michael Small:

Wait a minute. This may seem like really normal to you. To me, this is really surprising.

Tupac Shakur:

Right.

Michael Small:

This has happened to you personally?

Tupac Shakur:

Personally, yes.

Michael Small:

When you're sitting in front of your own house?

Tupac Shakur:

No, that happens like a lot of times. You don't see black men... We don't have houses. We have, like, apartment buildings. And so the equivalent to standing outside your house is standing outside your apartment building. Yeah. You know, hang out in front of the building, sitting on the stoop. That's how you talk. That's socialization, you know what I'm saying? They did it in "Our Gang," they did it in "The Little Rascals" and everything. But we can't do it. We can't all be in a group. We gotta be a gang. You know what I'm saying? We gotta be selling drugs.

Michael Small:

Is that something that happens to you, like it's happened once?

Tupac Shakur:

That happens a lot. See, what it is that, because there's no choices to be made, a lot of young black males are in the game, the dope game or the crime game or whatever. They're in the game. So they're illegal. So the police know this, and they use that to their advantage. That's when they work outside of the law. They're above the law. They get to do whatever they want, because nobody gives a fuck about a dope dealer from the ghetto, or nobody gives a fuck about some juvenile delinquent from the inner city. So that's how it go. You know what I'm saying? The police can say what they want and do what they want, and nobody's going to really complain, because who they gonna go to? Everybody knows the law doesn't work for us. And any n--- I can point out, any n--- in my crew will tell you it's happened. And when I say n---, I mean N-I-G-G-A, Never Ignorant, Getting Goals Accomplished. Not n---, n---.

Michael Small:

Never Ignorant...

Tupac Shakur:

...Getting Goals Accomplished.

Michael Small:

In terms of those incidents where they yell out things like that, what is it like? They'll drive by and yell things out the window?

Tupac Shakur:

They'll drive by real slow or they'll get out the car. It doesn't matter, whatever they want to do. You know what I'm saying? And it's like, when the police come around, that's why everybody's like... See, that's the one time the brothers can unite and everybody yells out, "Rollers!" or "Five-O!" So you know, 'cause I mean, nobody wants to be oppressed. God don't like ugly.

Michael Small:

Do you think the Oakland police are particularly worse than other police?

Tupac Shakur:

No, I think every police... I've not encountered a good police department. The only good police department is a black police department, that black people have put there. You know what I'm saying? We need, we can't be... that's just insane to me. That's just like, what if I got seven of my homies on the block and went and patrolled Beverly Hills? I don't know how they live. How can I... you know what I'm saying? How can I properly patrol those people? How can I keep the peace if I don't even know what their idea of peace is?

Michael Small:

There seem to be, to me, a lot of black policemen.

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

Are the black policemen as bad as the white policemen?

Tupac Shakur:

Worse. Some black policemen, they're in the force now. So they believe, you know, they believe they're brother enforcement. And what it is like, they done heard so many brothers come in and go, "Come on brother man, come on brother man, you know, that white dude beat me down, blah, blah," that they don't even listen anymore. Cuz that's what I was doing when I went to the... after I got beat up. They put me in jail and I was like, going to the brothers. I was like, "Yo, them cops just beat the shit out of me and they talk about "master," shit like that. And it's like, "Whatever. Get in your cell. Shut up. Get in your cell." You know what I'm saying? This is black cops, white cops. All cops are the same.

Michael Small:

Can we to through the exact incident that happened? Can you repeat it to me? Where were you?

Tupac Shakur:

Broadway and 17th, downtown Oakland. And I jaywalked. Walked across the street to my bank. Police stopped me, asked me for ID. "Where you going? Let me see some ID." That's exactly how they stopped me. "Where you going? Let me see some ID." So I froze up, went in my pocket, got the ID. I got three pieces, my bank book, social security card, my passport. They was like, "Well, what's your real name?" And I was like, "That IS my real name." They were going, "What is your real name?" And I just stopped answering them because, I mean, how stupid can you be? This is my passport, you know, my social security card, and my bank book. I'm saying that's my real name, Tupac. So they got mad. I got mad. I was like, "Why y'all harassing me with all the crime that's going on today? Why does it take two cops to apprehend me for jaywalking? What is the deal?" And they was like, "Don't worry about what we doing. You're gonna learn your place in Oakland." I was like, "I'm in Digital Underground, blah, blah." They said, "You're not above the law." And I ended up saying, "Well, fuck y'all. Give me my citation and let me be." Soon as I said, "Fuck y'all," they grabbed me, slammed me, put me in the chokehold, banged my face against the concrete, and I was unconscious. I woke up, cuffed up, with my face in the gutter. with a gang of people watching me, like I was the criminal. Then I spent seven hours in jail. Ironically, this is the day that my video was being debuted on Yo! MTV Raps. I missed that, because I was in jail.

Michael Small:

I don't think this is true, but I think people are gonna say it sounds like a publicity stunt.

Tupac Shakur:

I know, and that's why I am like I am. And that's why I'm happy you're doing this, because now I want people to know that, you know. I'm not just sitting out... I'm not just out there holding my dick cursing, you know what I'm saying? I'm not just going "Kill, kill, kill." This is not, you know, what I'm saying: "real n--- for life" shit. This is not that. I'm talking about true-to-life incidents, you know what I'm saying? And shit happens, and it makes you a violent person. It makes me a caged animal, and that's how I react. And that's how my lyrics are, in a state of emergency. 2Pacalypse Now. It's a state of emergency.

Michael Small:

How do you get out of jail?

Tupac Shakur:

I got bailed out by my people.

Michael Small:

Then what happened? What did you do?

Tupac Shakur:

Then I sued. I went to a lawyer. I told them I'm not having it. I told my manager that I'm not gonna write another rhyme, I'm not gonna go to another Grammy show, I'm not gonna do shit. I'm a big criminal until they deal with this. And he said, "Okay, wait a minute. I'll get a lawyer. We'll file a suit and we'll take care of it the right way." I said, "Okay." If not, what I was gonna do was get my hands on a weapon and I was gonna go up to the precinct where the guys work and just start doing some violent shit.

Michael Small:

But would that solve anything?

Tupac Shakur:

No, but see, that's how it is. You know what I'm saying? Everybody says that. It's OK for me to get beat down. But as soon as I talk about beating somebody down, it's like, "Will that solve anything?" I want young black men to see that the police is not untouchable. And I want police to see that they're not untouchable. And that a 20-year-old black man could come and snap some money out of their pocket. And that's what I want to do. I want them to pay me. I want them to buy me a house to take care of these kids. I'm trying to show now that it can work for you with this lawsuit. But see, the only reason it's gonna... it might work for me is because I got a little money and I can hire lawyers to do it. But the, you know, the average young black male can't do that. And the court appointed lawyer's a joke.

Michael Small:

I'm trying to anticipate what other people would say in reaction to all of this. So I'm trying to throw some of this in front of you and let you answer. I'm a case of a person who's been mugged five times by young black males. So... There is a feeling from the police that these are the people who are doing the mugging.

Tupac Shakur:

Right.

Michael Small:

And how do you answer?

Tupac Shakur:

I got the perfect answer for you. Check this out. Me, as a young black male, I've been fucked by white people all my life. All my unborn life. My whole people, my race has been fucked by a white person for all this time. Should I hate all white people? Should I strike back and kill? Should I rape every white woman because white men raped all the sisters? That's exactly how I feel. That's what the police do. Just because black people mug white people, that doesn't mean that every young black male got mugging on his mind.

Michael Small:

That's a great answer. Have you had any good experiences with cops at all? Have you seen cops do good things, help people in trouble, whatever?

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah, I mean, I guess, yeah, I've seen that. There are good cops, but... the majority are bad. And plus, since the good cops want to act like the bad cops ain't there, they become bad cops. So I have no mercy on no cop. Only cops I like is cops that don't speak to me. You know what I'm saying? Just ignore me, and I ignore you.

Michael Small:

But if I was in trouble, like when I got mugged, I called the cops.

Tupac Shakur:

Right. If I get mugged, I'm calling the cops. And they should come, because that's what I pay them for.

Michael Small:

Have you ever had to do that in any time?

Tupac Shakur:

No, but every time I've ever called the cop with anybody, it's always took a long time for them to come. And they always grab me first, but think I'm the one automatically.

Michael Small:

Do you think there could be a change in the way they're trained that could make things better?

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah, it's that power shit they start getting lost on. Plus you have to pay them right. Plus you have to treat them right.

Michael Small:

Oh, that's interesting.

Tupac Shakur:

All of those are factors, you know what I'm saying? I understand cops. They got to, you know, they're like... they're closer to n---s than people know. Because they got to deal with war every day. But see, that doesn't mean that they can take it out on everybody. And that don't mean that they can have this cold, you know, just talk to us like slaves. That's bullshit. Because nobody allows that to happen in the white neighborhoods. So why let it happen in the ghetto? Why can they talk to us anyway they want to and treat us anyway they want to?

Michael Small:

A lot of people I've been interviewing for the book say, "I used to sell drugs, or my friends are. The people I hang around with are." In your case...

Tupac Shakur:

With me, it was like, my homies... They loved me so much that they saw a spark in me and they knew I wasn't a dope dealer. And so they did everything they could to have me not sell dope. You know what I'm saying? I mean, I made so many fucking loans from dope dealers that I've never been able to repay because they're not here anymore. Because they saw it, you know what I'm saying? They would just go "Here..." you know? "Just make that album, mention my name." And that's how it is. And that's why I can hang around dope dealers. Because I understand. very, very well why they do what they do. And I don't want anybody blaming them until they can make an alternative. You know what I'm saying? Because if we go back through history, look what America as a nation was doing before they did this, before there was The Great Emancipator. They was going from place to place, kicking people's asses, passing out diseases. You know what I'm saying? And taking people's land. So I understand it's not that far from being a dope dealer. You know what I'm saying? So I think that as a race, a human race, we gotta correct these problems. But they didn't feel like we needed to be corrected. They're like, "Well, as long as we out..." They're out the dark ages. So let us stay. But we in the dark ages, man. We in this dope shit because we don't have no other option. If you could live in my neighborhood, a ghetto, for just one month, you'll be changed around. Just like "Trading Places" and all that shit they be doing. They know what they're talking about. It's the environment. You know what I'm saying?

Michael Small:

The people selling drugs, though, some of the greatest harm they're doing is against the community they're in.

Tupac Shakur:

Right, but you have to understand the state of mind that this young dope dealer is coming from. I call them soldiers, because they're soldiers. They're closer to war than any soldier in the armed forces. You know what I'm saying? They have to deal with the enemy on a day-to-day basis. You know what I'm saying? Walking around, seeing your people like zombies, and you're the one that's making them like that. That's not a good feeling. They know that. But it's like this. I can tell you so passionately because I've asked the question so many times. And they stump me every time. Because I go, "Why, why, why?" And they go "What else can a n-- do? It's the law of survival. Either you starve or you feed yourself." And the white man will not... and when I say white man, I mean white society. Not you as a white man, or I mean the white society. I mean all the Oreos, all the Mexicans, all the... every race. that wants to have that white man mentality. When they give out positions and when they give out product, they go by the young black men. We don't get a product to sell. You know what I'm saying? Even the little white kids got Boy Scout cookies and paper routes and shit. You know what I'm saying? Only product they drop off in our neighborhood is kilos of cocaine. And if somebody would take the time and look at the fucking entrepreneurship it takes to move the dope that n---s move... 'cause all they do is drop pounds off in the neighborhood. Trust me when I tell you. I know some of the largest dope dealers and they all tell me, "I don't know where this shit is coming from. I know it get dropped off though." Every time I start talking about culture and people and race, everybody goes, "Oh, but it doesn't seem so day to day. You know, it seems like, what an age-old question." But it's not like that. It's like... This little... all of that stuff fuels the day to day existence of the young black male. You know what I'm saying? It's these thoughts that go through your mind as you sit. You know what I'm saying? You don't even have somewhere to stay, man. How do you expect somebody to turn your product down when you don't have anywhere to live? You got a kid, you got babies, you gotta feed the babies. You know what I'm saying? Your wife is telling you, you loser, you fucking no good-for-nothing. You dropped out of school, you don't have a job. What are you gonna do?

Michael Small:

Are you still living in Oakland?

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

Do you live with family or do you have your own place?

Tupac Shakur:

I just got my own spot. It's an apartment. One bedroom. But you know, we fit. We make do.

Michael Small:

Ice-T said, "Get out of the ghetto. Leave it behind. Go make it somewhere else. This place is... leave it to go to waste." Chuck D is like, "Go back, fix it up, make it work." Do you have an opinion on all that?

Tupac Shakur:

My ideology is survive. However you can survive. If you get lucky enough and they let you move into a white neighborhood and you get you a big house, live there. But don't forget the n---s. Don't lock n---s out just to keep your ass there. Because if you stayin' there but n---s can't come, that means you can't be there long. So you know what I'm saying? That's just a clue. But I just happen to be in a cool neighborhood where it's, you know, both. It's real.

Michael Small:

There's both?

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah. There's n---s. If you go one block one way, you'll go to a ghetto, you go one block the other way. you'll be by the lake and shit, you know? So it's like, live where you can live, you know what I'm saying? But if you try to ignore the ghetto, the ghetto gonna come up and snatch your ass. I don't know how to make this sound like that. But unfortunately, that's what happened to you five times. It might not be your fault, but the ghetto snatched you. And that happened, you know what I'm saying?

Michael Small:

The other thing is like, okay, so what change needs to be made specifically?

Tupac Shakur:

Well, first of all, the sneaky shit is on the down low, nobody knows that rap is educating the whole race of people. You know what I'm saying? Now that the white kids that are coming up are coming up listening to the black experience. You know what I'm saying? Therefore, these people, once they get older, they're going to outgrow that. You know what I'm saying? Their parents are going to shake that shit from them and they're going to get a regular job. But see, when they get these jobs, they're going to be in a position to hire. And then when they're hiring and I walk in there, they're going to know who I am. You know what I'm saying? They're going to remember this young black kid that was with him. You know what I'm saying? A real black kid. Not the black kid they got on TV, and the black kid they make, but the real black kid, the one that watched your ass. You know what I'm saying? The one that talked to you, the one that kicked it with you, the one you had a lot in common with, the one you understood, and he'll get a job, and we'll have a better world, because we'll be understanding each other. Just like I can really relate to Guns N' Roses more than I think anybody. I love that. I love them. Because they're going through some of the same shit. You know what I'm saying? They talking about some of the same shit I'm talking about. But they just talking about their people. And I'm talking about my people.

Michael Small:

Okay, what can a rapper do? A rapper educates through his music.

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah, I believe in education, but I'm taking more of a spiritual route, you know what I'm saying? Education, that's bullshit because who can I actually educate? I can't do nothing but tell you my experience and hope that you grow from it. And that's all I do, you know what I'm saying? I have a lot of respect for Chuck D and I have a lot of respect for Ice Cube and all of these people. But they can't do nothing but what I'm doing. Telling people their experience or the experience they got from somebody else. That's all reading is. You know what I'm saying? So I might as well use my experience. It's been real rich. If we would just use our life experiences and talk about that, that's how we can heal this nation. 'Cause you can go, "Oh look, he's doing the same shit I'm doing." You know what I'm saying? "He feel the same way I feel."

Michael Small:

A lot of the people I've been speaking to, like Kid and Play, I think, brought uniforms for a local team. Queen Latifah's giving money to a boys club. These are things that they think will help.

Tupac Shakur:

I got my own program now.

Michael Small:

What is it?

Tupac Shakur:

It's called the Underground Railroad. And I think that it shows that I'm not just... I don't wanna just give kids money. And I'm not. I'm doing more than that. I'm taking on the full responsibility. I got like a kids group, a female, a black female group, and a female and a guy who sing. And we're all a family. And we meet once a week. I meet with the kids once a week. We've got like a boys club thing where we go to the movies, we go out, we read together. They tell me about some of their experiences, things they go through and I make rhymes about it. They learn it, they do it in the studio. You know what I'm saying? They're learning brotherhood, they're learning unity, they work together, they learn how to express themselves, how to communicate, everything. And now ever since I've been working with them, they all been doing better in school. So they also learn how to get along in society. Yeah. So that's the real thing, you know what I'm saying? I wanna, this is the difference. I know it's a difference when a kid's mother call me and tell me that a doctor, a doctor, said that her child cannot retain things. And I said, "No, you must be talking about another kid because he just learned three rhymes in three days." I mean, I'm talking about results. And that's the real thing, you know what I'm saying? That's the real thing. And that don't have to be in the papers for me to do that. You know what I'm saying? I don't have to be calling every newspaper and say, "Guess what I'm doing?" Just do it. Just like Nike say, just do it.

Michael Small:

And it's called the Underground Railroad? Yes. And how many kids are involved with it right now?

Tupac Shakur:

Right now, I got a lot. Because now, as a matter of fact, today, a friend of mine that I knew from Baltimore way back in the day, I'm flying... He's flying out here today to live with me. And he's joined the Underground Railroad. We got people in New York, all over, Atlanta. It's not like a set thing. It comes out of my house in my heart. You know what I'm saying? Whoever I come in contact with, I try to do as much as I can. I turn my home into a train and I use the studio. It's just like they stay with me until they get signed. You know what I'm saying?

Michael Small:

But like at the meetings you're talking about, like how many kids would typically be at those?

Tupac Shakur:

The meetings are like, they're not like meetings where you come and do a meeting. We like, we hook up every weekend, just the kids that I work with, just the ones that are in the group, and we go to the movies, we talk. It's like, how many kids? Eight?

Michael Small:

Did some kids then move on and you take in new kids?

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah, once they get, once these kids get signed, we'll still work with them, but then we'll concentrate again on the new crop.

Michael Small:

So the goal is to get them signed as rappers.

Tupac Shakur:

Get them signed as rappers or get them on the high school, you know what I'm saying? Or get them to where they start working with kids. You know what I'm saying? Where they start working with people. Just like Harriet Tubman from the South to the North, I want to take them from illegitimate to legitimate, whatever way I can.

Michael Small:

You said you're part of Digital Underground.

Tupac Shakur:

I'm in Digital Underground. I'm a member of Digital Underground, but what it is that I refuse to... I don't want to play myself, you know what I'm saying? I feel as though I should stand on my own merit, and anybody who knows Digital Underground should know that I'm in the group.

Michael Small:

Do you perform with the group?

Tupac Shakur:

Yes.

Michael Small:

It seems so strange that I listen to you and you're really full of fire and politics, I think, and Digital Underground is one of the more have fun, happy type groups. So why did you want to get involved with them at all?

Tupac Shakur:

Because... This Underground Railroad thing that I'm doing, it's all a personification of what Shock did for me. He took me in and he got me to legitimate, you know what I'm saying? He made me a legitimate person. And he did, he made me an honest man. He did something and had faith in me, when nobody did, you know what I'm saying? When nobody cared. I was just one more black kid with no money. Just one more. Just one more rapper. You know what I'm saying? And he saw deeper than that and he helped me and he got me to this point. And that's truly, to me, the most beautiful thing you can do for a human being. Not give them a glass of water, but show them where the wishing well is. And that's what he did for me, and that's just a great thing. And so, I mean, ever since then, I pledge my allegiance to Digital Underground for life.

Michael Small:

Just another thing, just about this whole black-white relations thing. I mean, Digital Underground has a white DJ. Right. Is that...

Tupac Shakur:

And that's my n---, you know what I'm saying? These is my n---. It don't matter, you know what I'm saying? We broke that wall. That's my man. That's my homie. It's like that. And not because he's white. And he's not my white homie. He's my homie. You know what I'm saying? When he acts white, I tell him, "You're acting very white." You know what I'm saying? And he tells me, "You're acting very black." You know, we get along. We really get along. In a real sense. And it's not a black and white thing.

Michael Small:

Because you were part of the Humpty-Humpp song, does that mean that you... ended up, I mean they made some big good money off of that...

Tupac Shakur:

Oh I didn't make that, I didn't make money like that. I made a little bit of money off "Same Song," you know I got my little cut from that. But which is really little bit. And then I signed my own contract with Interscope Records for my own solo album and I got a little bit there. You know I've been getting a little bit, but what little bit I get I share. So I think because I do I'll get a little bit more.

Michael Small:

You got some money for Juice.

Tupac Shakur:

But that was a low budget film.

Michael Small:

How did you get the role in Juice?

Tupac Shakur:

Spontaneously walked in and asked to read for the part.

Michael Small:

Where? In LA?

Tupac Shakur:

In New York. Read cold for it. Money B was reading for a part. They had been asking him to audition for a character and I just went with him. And I was dressed in black and I was like, "Can I read?" And they was like, "Well..." and I was like, "Can I read?" They was like, "Good."

Michael Small:

What part did you play?

Tupac Shakur:

I played the villain, Bishop.

Michael Small:

Did you enjoy it?

Tupac Shakur:

I didn't enjoy it at the minute, but afterwards I loved it.

Michael Small:

Because why?

Tupac Shakur:

All the work and all the hypocrisy of Hollywood.

Michael Small:

Oh, like what?

Tupac Shakur:

The hypocrisy. Okay, like... You know, I'm real true to my words, and so when I went to New York, I got a lot of homies out there. So I would kick it with some brothers from out there. And we was doing a black movie about young black males. So I figured it's only right that I hang around young black males while we do the movie, you know? And they come to the set and watch the movie, being made about you. And the other... some of the other actors would bring like, you know, what I call new n---s to the set. T he manners, the ones that come from prep school and all of that. And that's who the producers wanted them to see me with. You know what I'm saying? And that's who they wanted. And that was cool for them to be there. But soon as I had some n---s on the set, everybody started freezing up. And so they would always, you know, harass me about that. Then I got robbed on the set. This guy went in my trailer and stole from me and I knew he did it. You know what I'm saying?

Michael Small:

So it was one of the people you brought on the set?

Tupac Shakur:

No, some other guy from that neighborhood, who had robbed me. You know what I'm saying? So the film people thought they was teaching me a lesson for being so nice to n---s that they wasn't going to reimburse me at first. And they just like writing it off. So I was like, "OK, well, I'll take justice in my own hands." And I got some of my n---s, the true n---s, and we went and found the little n---, N-I-G-G-E-R, who stole from me and beat his ass. Right there, one block from where they was filming the movie. Because I'm a true n---, not a fake film n---, a true n---, and you cannot rob for me. And so he got dealt with. And they didn't like that, you know what I'm saying? And so I got a little, I got like... you can see I'm fiery like, you know what I'm saying? So they didn't like that, and they spread a little, you know, they spread that all through the little... they spread it all over, everywhere I went, that followed me. You know what I'm saying? But that just makes me more how I am.

Michael Small:

This guy who stole from you, did he come on the set with your friends?

Tupac Shakur:

No, he just was one of the kids that... you know, when a young black male comes up to me, like I said, I don't treat him like a criminal. "What's up, how you doing?" Yeah. So we talked and talked, you know what I'm saying? And he just was, he came and was there. We was filming on location in the street.

Michael Small:

Totally switching to a different topic. Where did you grow up?

Tupac Shakur:

I grew up in the Bronx until the end of junior high. I went to Baltimore. Went to high school there, in the ghettos of Baltimore, and then moved to Cali.

Michael Small:

But you were at the High School of the Performing Arts?

Tupac Shakur:

At Baltimore.

Michael Small:

And did you graduate from high school?

Tupac Shakur:

Never. Got to my 12th year. I went to The School of Performing Arts, got to my 12th year in a regular high school in California. They wanted to leave me back because I had too much arts credit and not enough for what they felt like I needed, like physics.

Michael Small:

So you moved here when you were in your 12th grade?

Tupac Shakur:

Yeah. And they thought I needed more physical ed instead of fucking drama. So I wasn't with that. I didn't feel like I needed the school system to tell me whether I was intelligent or not, whether I could make it in this world. So I'm out to prove them wrong. I don't tell anybody else to do that.

Michael Small:

What do your parents do?

Tupac Shakur:

What do they do? Yeah. My mother is in recovery right now. And my father's deceased. But my mother was a great, great Panther, great Black Panther. She was one of the Panther 21. My father was a gangster. He died.

Michael Small:

How did he die?

Tupac Shakur:

Freebase. Heart attack from freebase.

Michael Small:

Did you ever get involved in drugs at all? I know you said that the drug dealers helped you from getting to selling it, but did you ever dabble in it yourself?

Tupac Shakur:

No. I mean, it depends on what you call a drug. You mean, like cocaine?

Michael Small:

Yeah.

Tupac Shakur:

No. Never. Was never one of my things.

Michael Small:

But marijuana's OK, I think.

Tupac Small:

Yep. Marijuana is, you know...

Michael Small:

I hear a lot of history from a lot of people I've spoken with. And I guess the question is, where do you get your history from?

Tupac Shakur:

My mother was a Panther, so she told me a lot. I listen to a lot of old brothers, you know what I'm saying? I listen to them talk. The veterans, I listen to them talk. My grandfather, Geronimo Pratt, he's a political prisoner in San Quentin. He's wrongfully in jail. He tells me things. Mutulu Shakur is my stepfather. Assata Shakur is my auntie. You know what I'm saying? I come from a rich, rich line of Panthers and straight up revolutionaries. All of these newborn rappers who keep spittin' all this "black, black, black..." they saying all that shit, but you know, they ain't do shit for my aunt, my mother, my father, none of them, and they the ones that... I was listening, watching them say thank you to Miss Assata Shakur, thank you to Mr. Matulu Shakur. But to thank him, they should have looked out for his motherfuckin' family. That's how it's so much rhetoric within our own community that that's why I have no tolerance for it in the white community. Because I had to deal with my own.

(Pause in interview)

Michael Small:

One quick pause here to mention that even though it was a year before the 1992 presidential election, Tupac and many of us were already worried about what was going to happen. A white supremacist, neo-Nazi named David Duke, had announced that he planned to run and he was getting a lot of press. So here's what Tupac had to say about that.

(Interview resumes)

Tupac Shakur:

I got a forecast and a prediction for this whole country. And I mean this from the bottom of my heart. And I hope that as a journalist, you put this as I say it. If David Duke is elected for the office of the presidency, I promise, me, myself, I'll cause bloodshed to this world. There will be bloodshed. I'll be one of those people that shoot places up. I guarantee. I'll leave my rap career behind, and I'll become a violent terrorist. I promise you, and I'll bring this country down, however I got to. That's disrespectful to any black soldier that ever served in the armed forces, any Jewish soldier, you know what I'm saying? Any minority soldier. You just got to see it as fucking a stab in the back. He shouldn't even have television time. They didn't let Huey Newton have that television time, you know what I'm saying? Malcolm X, you see the way they used to do? They saw Malcolm X as a racist. at that time. See now, he was the racer at that time. You think they were doing what they do to David Duke? David Duke is a fucking celebrity.

Michael Small:

According to him, black people are getting all the jobs. The poor white people aren't getting the jobs. You know, I heard people on the radio during the election time, they were calling up and saying, "Look, I've got calluses on my hand, and I went in and I tried to apply for jobs, and they said, we're only hiring minorities." You know, so these people would say there are lots of opportunities that (black) people aren't even taking advantage of.

Tupac Shakur:

And for these people, I understand. I can relate to a poor white person more than I can relate to a rich black person. You know what I'm saying? It's not really like that. I mean, I'm down for them too. If they down for me. But they have to understand... if they take the point and position that the black man is taking everything from them, they're going to be an enemy. You can look through history and see that's a goddamn lie. N---s haven't begun to get what we deserve. And when I say n---s, I mean N-I-G-G-A. Never Ignorant, Getting Goals Accomplished. We haven't begun to get what we deserve. Therefore, how can we be getting all the jobs? These little bullshit jobs... I want jobs like Rockefeller and Trump.

Michael Small:

What do you feel about affirmative action?

Tupac Shakur:

I'm not familiar with what that is because I've never had a job.

Michael Small:

Did you try for some and didn't get them?

Tupac Shakur:

I tried and I wouldn't get them. And then the little ones that I would get were so menial that after a day I'd be quitting. Because I was like, I was always writing and I would write while I was working, you know? Like if I had to sweep, I'd sweep up and then I go write on my spare time. And he'd get mad. "On the clock, you can't write, you can't think while you work for me." And I just left. I was like, "Well fuck you." That was the last job. To me, you working should not mean more than your heart. I think we owe each other as a race to really get to the bottom of where we, you know, find ourselves. I think if everybody finds themselves and they have harmony within themselves, it'll be harmony in the world. You got to find your karma, your own personal karma, what you're meant to do. When you do that, you'll be, you know, you'll be good for this world. And that's what I feel like. And so nobody can interrupt that. Not work, not drugs, not police, nothing.

(End of Tupac Shakur interview.)

Michael Small:

And that's it, my interview with Tupac. In the months after we spoke, there were a couple of surprises. One is that Tupac filed a $10 million lawsuit against the Oakland police, and he actually got a settlement. He got $43,000. Most of that went to pay his lawyer, but this was a victory. His point got made. Also 2Pacaclipse Now wasn't a huge hit at first. It took four years to go gold in 1995, which is a surprise when you think of the demand for all his albums since then. Anyway, after all this, we've reached the part of every episode that I don't like so much. We need to look at what I've saved and determined if I can throw any of it out.

Sally Libby:

Well, we know the answer to that.

Michael Small:

Maybe there'll be something. You remember in our last episode, I threw out a little bit. But I believe that it is a sign of my sanity that I have no intention of throwing out an audio tape of one of Tupac's first interviews of his solo career. Does anyone want to defy me on that?

Sally Libby:

I bet you could get big money on eBay with that.

Michael Small:

Well, I'm not looking for big money on eBay. I'm looking for somebody may want to preserve this. And if they do, they'll get in touch with me. April, do you agree that I keep the tape?

April Beezer:

I agree.

Michael Small:

Here's an interesting thing. The press release that I wrote to publicize my book. I don't know if either you're going to remember this, but the headline on the press release is Dan Quayle has done it again. Sally, who was Dan Quayle?

Sally Libby:

He was vice president for Bush senior.

Michael Small:

This press release says: "Dan Quayle is making a habit of attacking the wrong people. The latest target of his misdirected criticism is the rapper Tupac and his 1991 album 2pacalypse Now. Speaking in Houston, Quail denounced the record because a gunman who fatally shot a Houston state trooper claimed to have been listening to 2pacalypse Now before the shooting. Quail announced that distribution of the album is an irresponsible corporate act." Then I go on to say all these positive things about Tupac. They later found out that the shooter was not actually listening to 2pacalypse Now. I think it would be wrong to throw out this bit of history. I'll find some other things here that can go. These are notes that I sent in when People Magazine was doing the story about him when he was arrested for sexual assault. April, have you ever heard of a rapper called Tragedy?

April Beezer:

No.

Michael Small:

He was Tupac's friend. He was Tragedy the Intelligent Hoodlum. and he was based in Queens. And April, he said something about Tupac that's really similar to what you said. Here's what he told me. (Reading) There's a war going on right here in America for young black males, and he's fighting the enemy, the police. All he's seen is that cops kill his friends and brutalize people. That's why he hates the cops. If you grow up in that environment and you're too nice, you're gonna get fucked. In order to survive, you gotta always be on the defense. Other people can't understand it because they don't live under the fucking red dot. They don't live under the gun. We do.

April Beezer:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

Then Tragedy says: (reading) He's not a bad individual. The problem is that he's trying to be real in a fake world. It's eating him up inside. He's struggling with himself and he's putting himself in some fucked up situations because of it. You're going to have bad elements around you, especially when you're young and making money. I do feel he should lose some of the crowd he's around. There's a time to be a warrior and there's a time to grow and learn. And if Tupac doesn't realize the warrior time is over, then he's going to self-destruct. I don't want that to happen to him because I love him.

April Beezer:

That's what happened to him.

Michael Small:

I think that interview is worth keeping.

April Beezer:

Yeah.

Michael Small:

I have a few other things I wrote about Tupac, which I'll post on our website, but I also have these articles that other people wrote about him and these I am going to throw out. Here we go. Boom. Into the trash. (Plunk sound.) So, okay, I didn't throw out a lot. As usual. I know, I let you down again. And we're almost done here. But first I need to direct your attention to someone else. His name is Kenny Cooper, and he is living out some of Tupac's best ideas. Kenny was in my writing class with April at Avenues for Justice. But now he runs Believe Music Studios in the Bronx, where April recorded her raps. It's a wonderful place where they're producing great music. April, can you talk a little bit about what Kenny is doing for the community?

April Beezer:

Yeah, shout out to my bro Kenny. Basically, he's seen the community needs an alternative. So instead of a program, he made a studio. He got other young people to be engineers, producers. He worked with all ages, nine, eight, 20, 50. Saturdays is youth workshop. They do artist development classes. It's really good for us.

Michael Small:

Does this not sound like Tupac's Underground Railroad that he talked about? He was helping kids record to give them a positive experience. And that is exactly what Kenny is doing in the Bronx right now at Believe Music Studios, continuing this thing that Tupac wanted.

April Beezer:

Yeah.

Sally Libby:

It's great.

Michael Small:

We also want to give a big thanks to Dr. Dre for sharing his wisdom with us. Big thanks to Avenues for Justice, the alternative to prison program in New York City that gave a second chance to April and many other wonderful young people. If you support Avenues for Justice, it is a truly beautiful way to honor the memory of Tupac. And you can do that at avenuesforjustice.org. Sally, do you have anything to add?

Sally Libby:

Well, we pulled together a list of all the best movies and TV shows. books and news sources about Tupac. And you'll find a link to the full list on the page for this episode on our website at throwitoutpodcast.com. And while you're on our website, we have two episodes about the rapper Eazy-E of NWA. If anyone missed those, they are also at throwitoutpodcast.com.

Michael Small:

April, thank you so much for joining us.

Sally Libby:

April, you were fantastic.

April Beezer:

Thank you. No problem. Thank you for having me, guys.

Michael Small:

I'm sorry I didn't do any better at throwing things out in this episode. But there's always hope for the future, isn't there, Sally?

Sally Libby:

Hope never dies.

Michael Small:

Especially not when we're listening to our rockin' theme song, which we'll do right now. It ain't Tupac, but it's still special to us. Bye, April!

Sally Libby:

Bye, April!

April Beezer:

Bye, guys!

[Theme song begins]

I Couldn't Throw It Out theme song

Performed by Don Rauf, Boots Kamp and Jen Ayers

Written by Don Rauf and Michael Small

Produced and arranged by Boots Kamp

Look up that stairway

To my big attic